- Home

- KNMA, Saket, Delhi

KNMA, Saket, Delhi

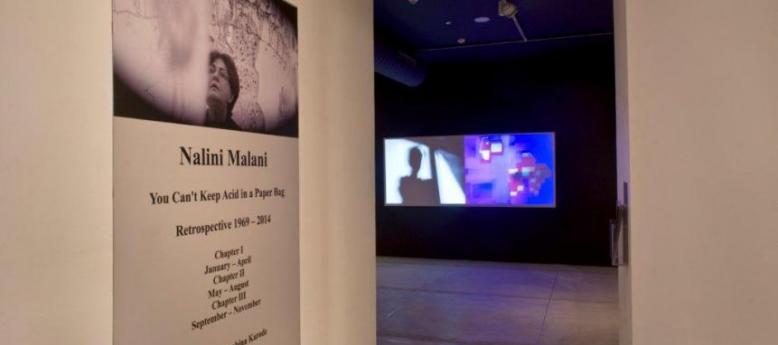

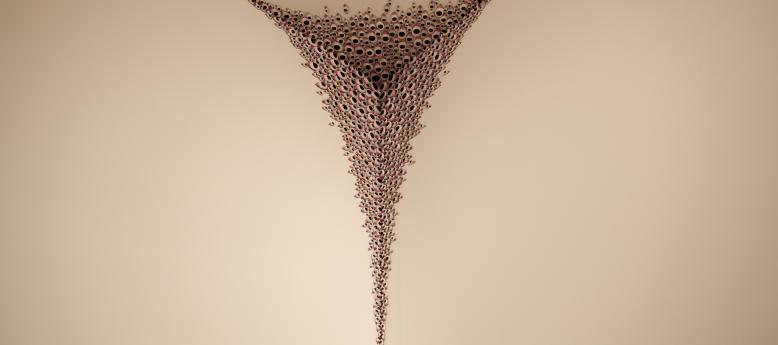

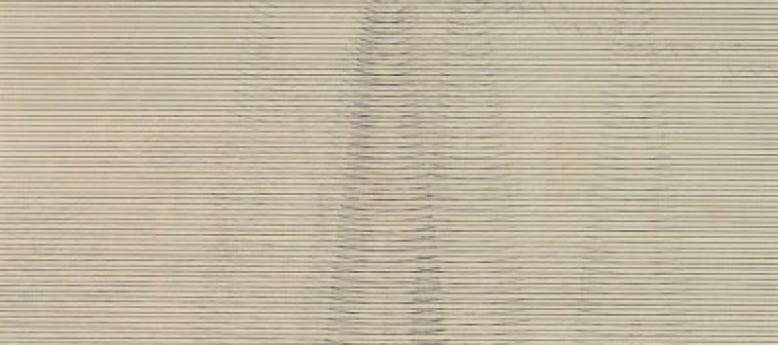

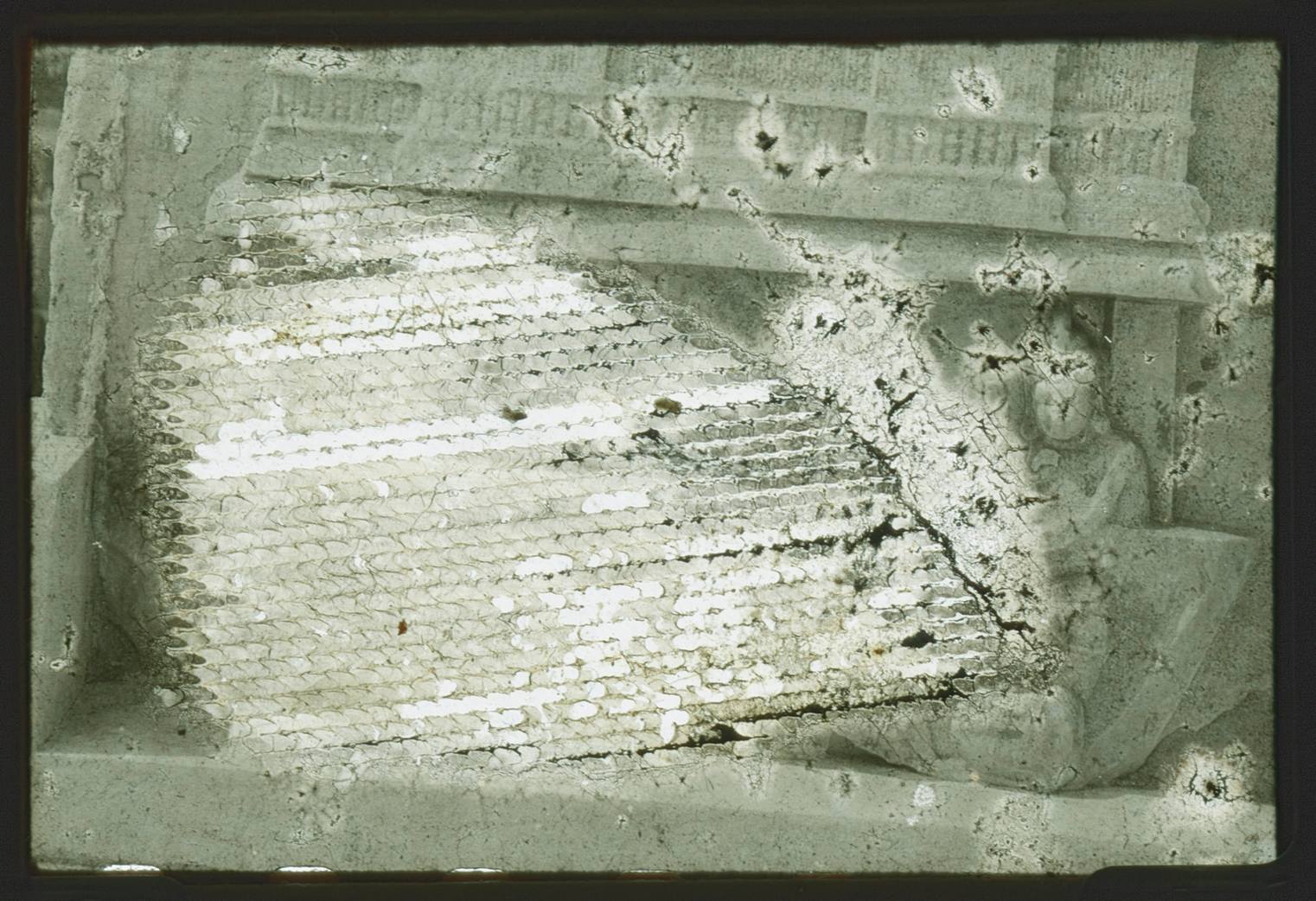

The show Line, Beats and Shadows presents artists Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh and their eclectic interpretation of abstraction. The artists use an array of material, often disguising it to appear in a different form. Ayesha Sultana masquerades fragile paper into metal, her aesthetics drawn from the visuals of Dhaka’s shantytowns marked by disparate class conditions. On the other hand, Prabhavathi Meppayil’s works of metal parts marked by an economy of means harmonizes modernist practices with traditional craftsmanship of goldsmiths in southern India. Sumakshi Singh uses the aspects of nostalgia and memory to recreate domestic architectural spaces using lace embroidery. In place of brick and mortar, the fragile space breathes a new life as people inhabit the space while engaging with spectral cob-webs of past memories. Encapsulating Lala Rukh’s parallel photographic practice are a suite of six works on display which were recorded during Lala’s travels across South Asia between 1992 and 2005. Laced with minimalism, a philosophy which she carries throughout her studio practice, each series of small works reflect time-captured tranquil topographical views of water bodies, devoid of people or beings.

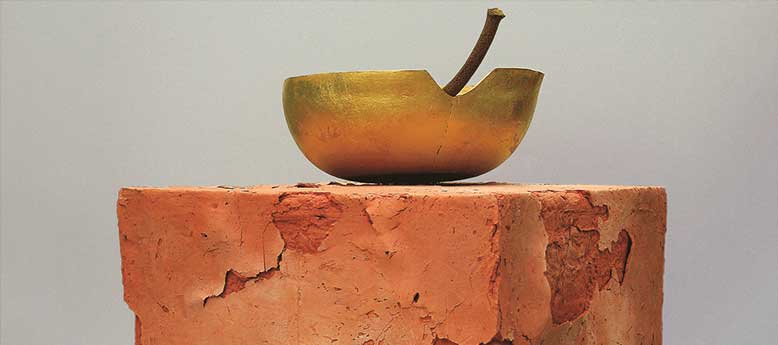

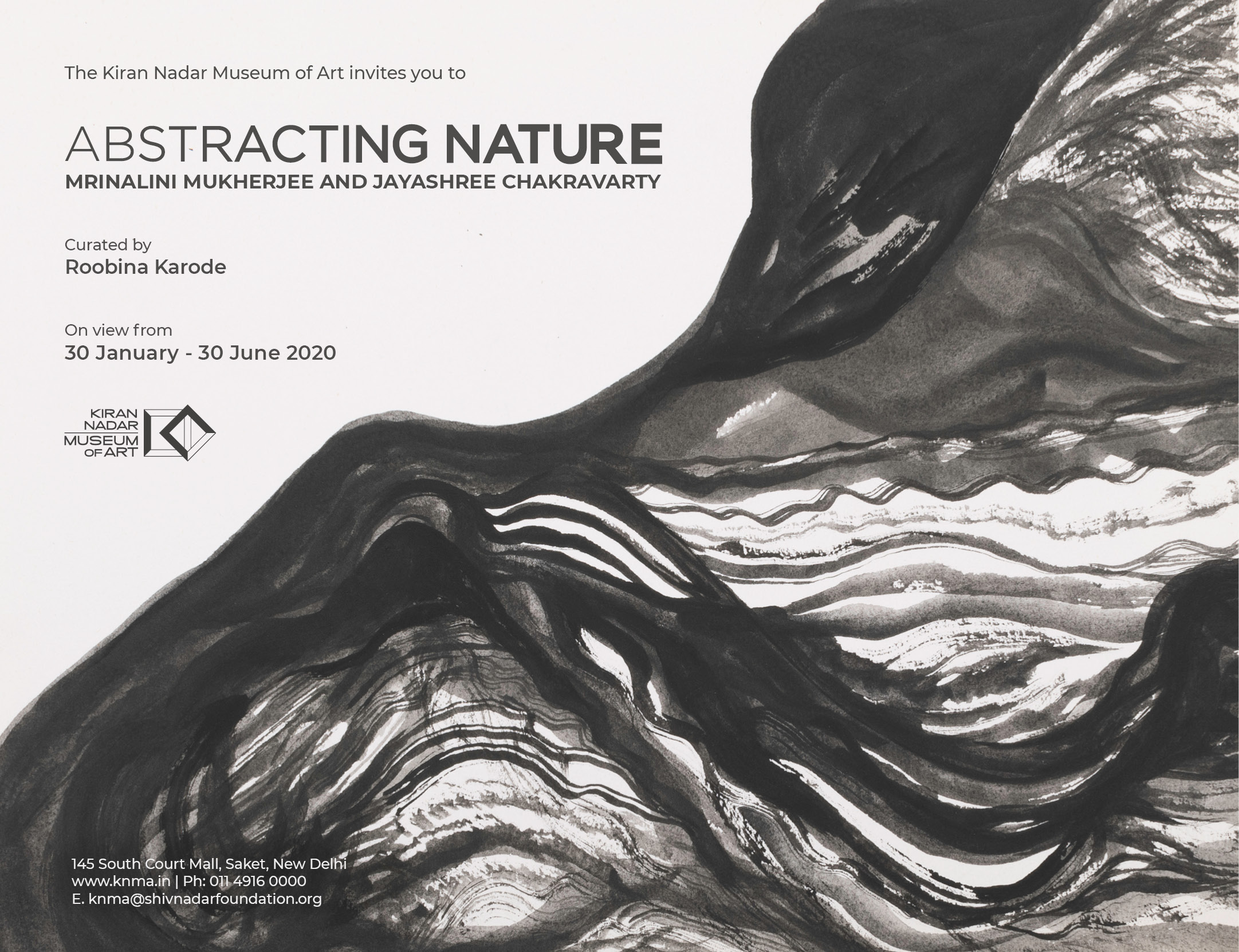

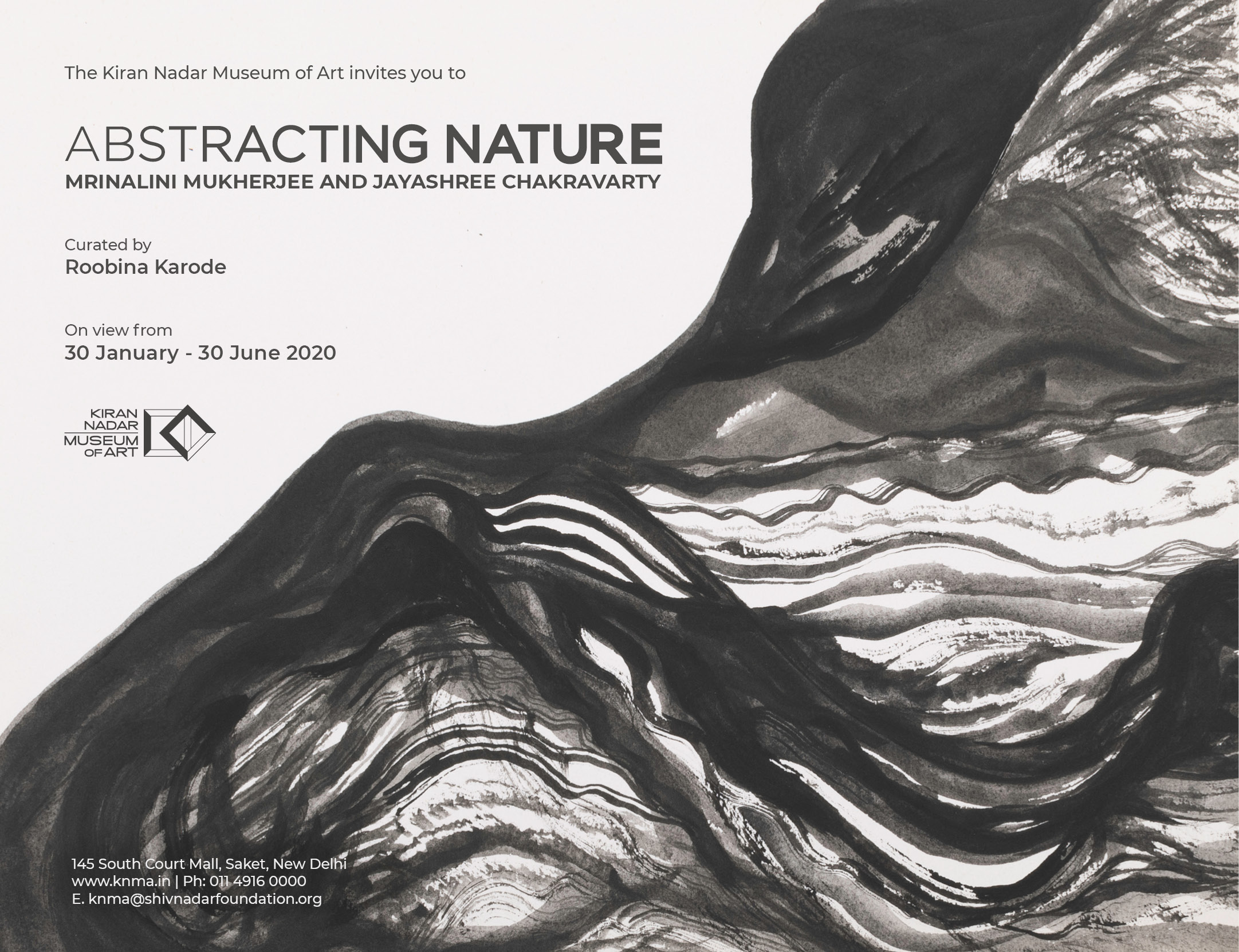

A mirroring of approaches is seen in the show Abstracting Nature as the artists Mrinalini Mukherjee and Jayashree Chakravarty amalgamate myriad objects found in nature into their own oeuvre. Seeking solace in the serenity of nature also deeply resonates with the artists’ philosophy. A corpus of drawings, etchings and watercolour produced by Mrinalini Mukherjee showcases the artist’s long standing connection with nature including her self-absorption in the flora and fauna in her immediate environment. A careful look at these works reiterates Mrinalini’s perception of nature- where cords, knots, tangles and twists become apparent as her unswerving preoccupation. In addition to these work, Mrinalini’s bronze piece and her hemp sculptures crafted by knotting jute ropes/ fibres into sculptural material through enormous muscle power, energy and time are displayed.

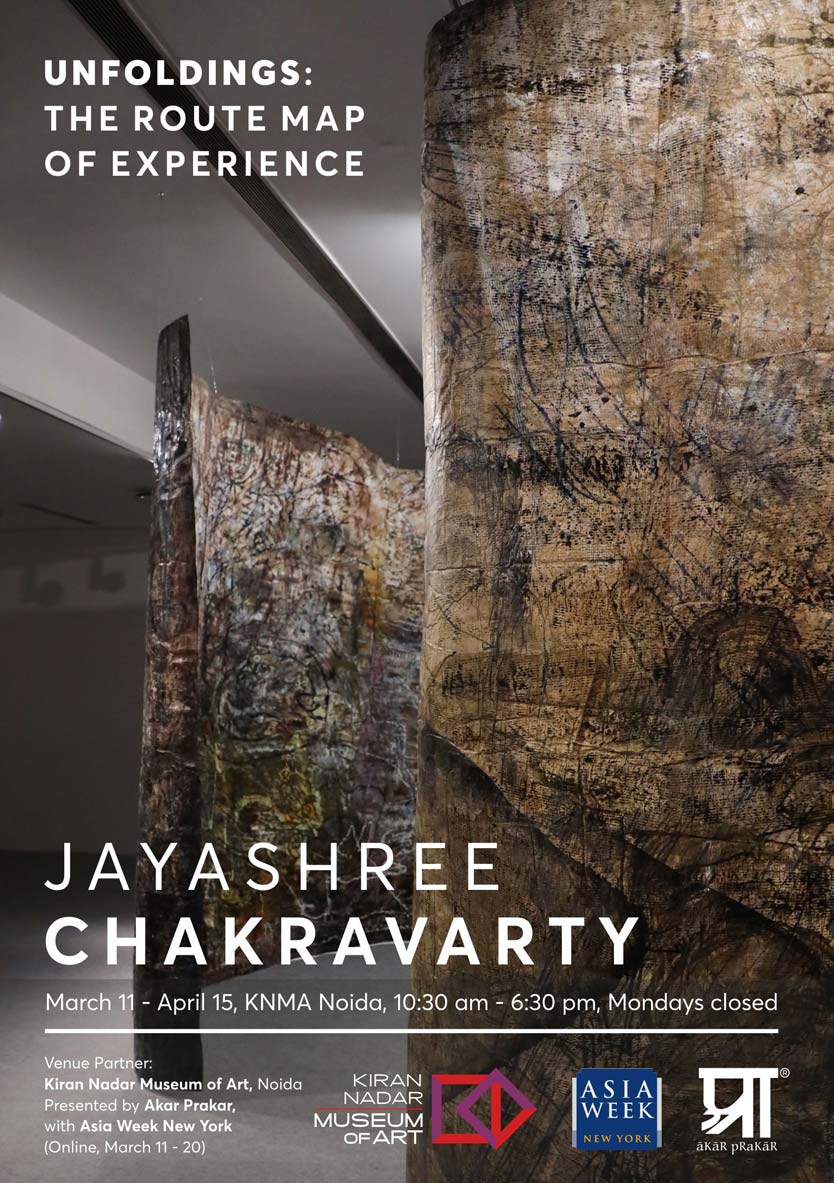

Over the last three decades or more, Jayashree Chakravarty’s art practice has addressed the exigent situation of shrinking natural habitat and water bodies in ever-expanding Indian cities. Jayashree through her works reminds us that the earth is continuously being pushed towards a precarious edge, where the threat of daily damage has taken on precipitous dimensions. Through poetic evocations, she weaves into her personal vision, the need for environmental balance and resurrection. Nature continues to be the subject as well as the substance of Jayashree’s art. Her works draw sustenance from the organic materials she puts to use, collecting dry leaves and dry flowers, twigs and delicate branches, roots and medicinal seeds, and now, crushed eggshells as well, weaving and mending, as if the ruptured fabric of life.

A thought-form part of the Young Artists of Our Times series Devised by Akansha Rastogi

Kush Badhwar + Alexander Keefe + Vidisha Fadescha Anish Cherian + Simultaneous reading of Paul Lafargue's The Right to be Lazy and Aman Sethi's A Free Man

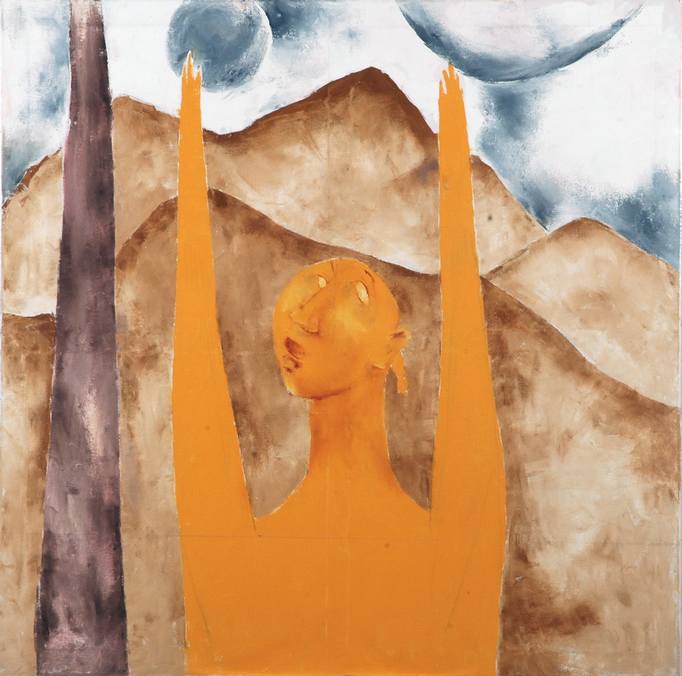

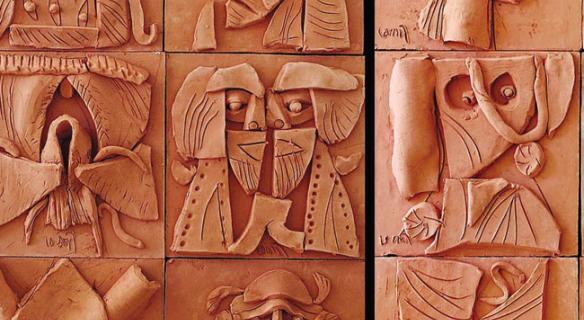

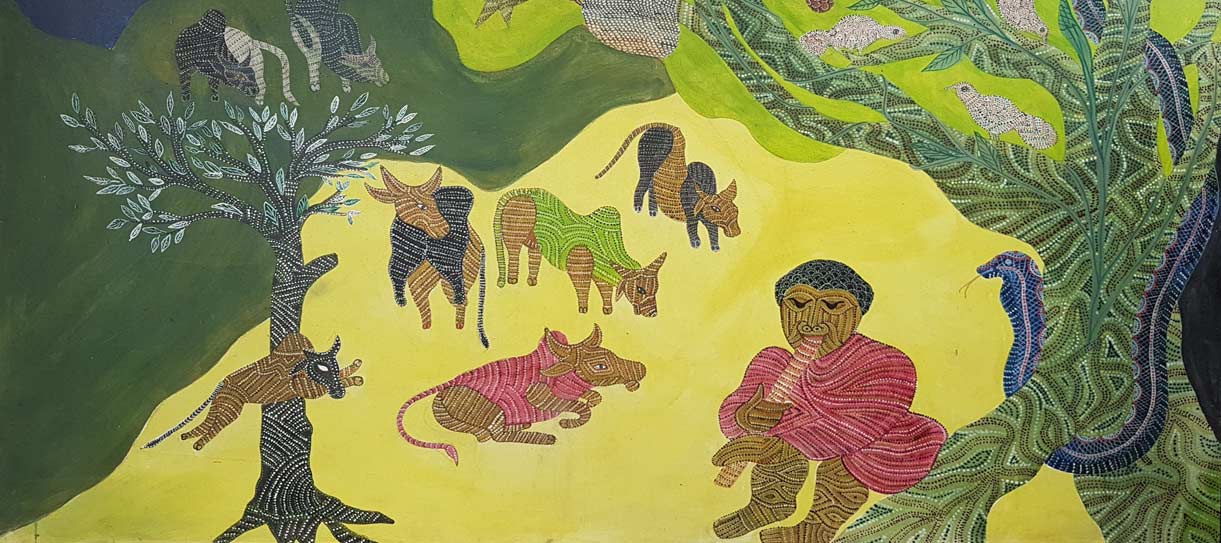

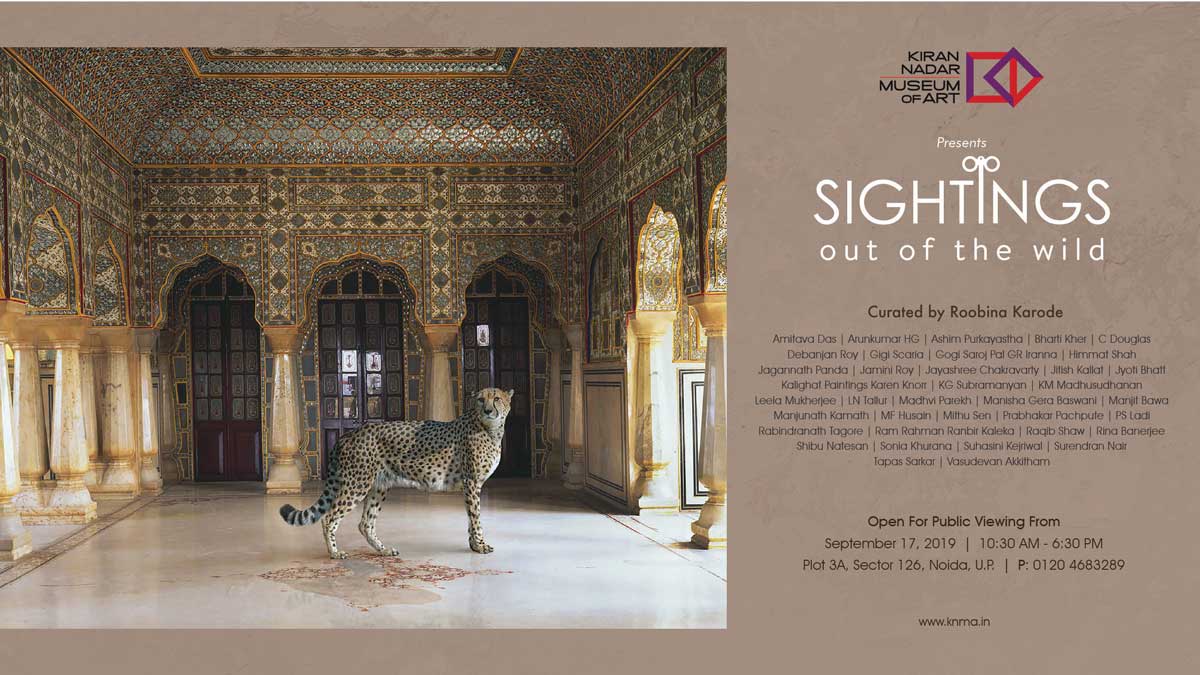

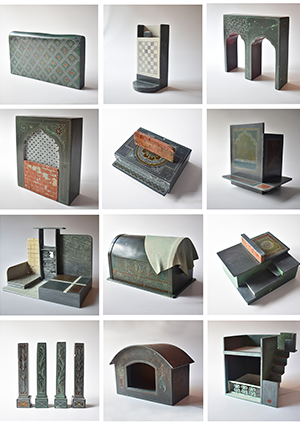

New Delhi, December 9, 2019: Iss ghat antar baag bagiche is an homage to Haku Shah (1934 – 2019), the reticent artist who grew up in an environment inspired by Gandhian thoughts and philosophy. We remember him as a painter, photographer, crafts archivist, an empath with a cultural polyphonic affection, well-known for his collection of artefacts of vernacular arts accumulated in the course of his extensive research and travels across India. Haku Shah meticulously documented varied cultural expressions of the rural arts and crafts, objects, techniques and processes of making. Drafting almost a new form of practice in post-independent India, with a strong educational focus. A cultural anthropologist with an archivist’s zest and values, his contribution to the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad, Shilpa Gram in Udaipur and several path-breaking exhibitions, remains unique. Mentored by artist-pedagogue KG Subramanyan, Sankho Chaudhuri and NS Bendre at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda, Haku Shah’s artistic passage, sought and created harmonious relationship between object, technique and concept.

Around eighty works from the Haku Shah archive including paintings, terracotta sculptures, textile scrolls, books, journals and periodicals will be displayed in the exhibition. Moving between miscellanea of mediums from oil on canvas, mix media collages to colour pencil and ink drawings on postcards to Shah drew from an assembly of cultural references. From 15th century Bhakti and Sufi poetry and verses to more recent literature, music, creative and social expressions the works carry a gamut of both dynamic and dormant avenues for interpretation. The exhibition brings together works from several series and a few that are being exhibited for the first time. It includes his collaboration with musician and vocalist Shubha Mudgal which resulted into the exhibition Haman hain Ishq (2002), the other series being Noor Gandhi Ka Maeri Nazar Main(1997), Nitya Gandhi / Living Reliving Gandhi (2004) and Maanush (2007) that reflects on humanism, embodiment and disciplined pursuit of Gandhian values and processual politics.

Born in the village of Valod, Gujarat to Vajubhai and Vadanben Haku Shah grew up in a region that imbibed a nationalist fervour and propagated the Gandhian way of life, having being located near a Gandhi ashram and centres of Satyagraha in a pre-independence scenario. Shah pursued his education from the Faculty of Fine Arts; Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda 1955-59. He had begun drawing at a young age, copying portraits of Gandhi in tune with the nationalist trends. The interdisciplinary and free atmosphere at Baroda initiated a foundation for his larger practice. After completing his fine arts degree in Baroda, Haku Shah taught at a Gandhian Swaraj ashram, Vedchhi in Surat district of Gujarat, and since then the handspun yarn became an important expression of his artistic persona. Dr. Stella Kramrisch invited Shah to curate the seminal exhibition “Unknown India” while he was associated with the National Institute of Design (NID) in 1967. The tribal museum at Gujarat Vidyapeeth in Ahmedabad, which was founded by Mahatma Gandhi, was a site Shah engaged with. He taught at the School of Architecture, Ahmedabad for many years, aside being Regent Professor at University California, Davis. An awardee of honours like Padma Shri, Kala Ratna, Kala Shiromani, Gagan Abani Puraskar and fellowships like the Rockefeller Fellowship and the Nehru Fellowship, Shah implemented a parallel modernity, inspired by vernacular philosophies.

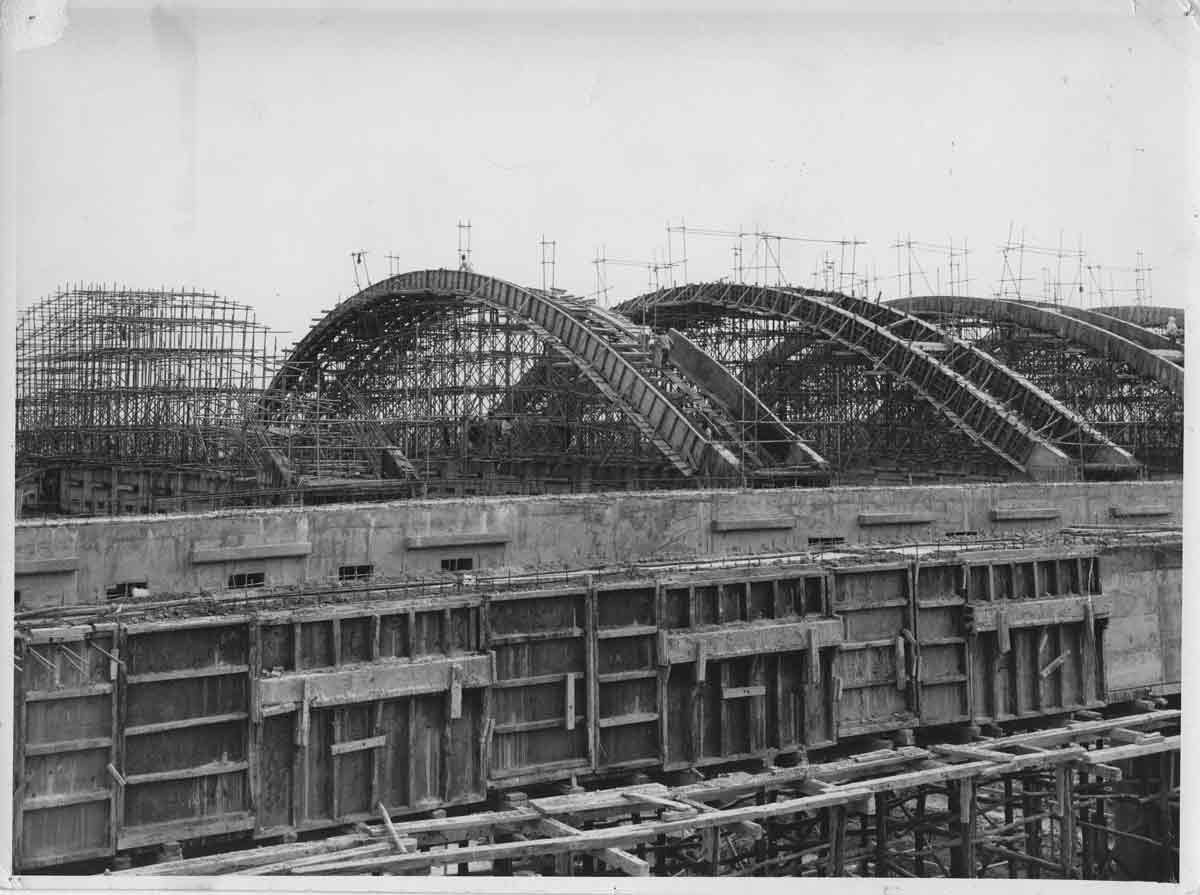

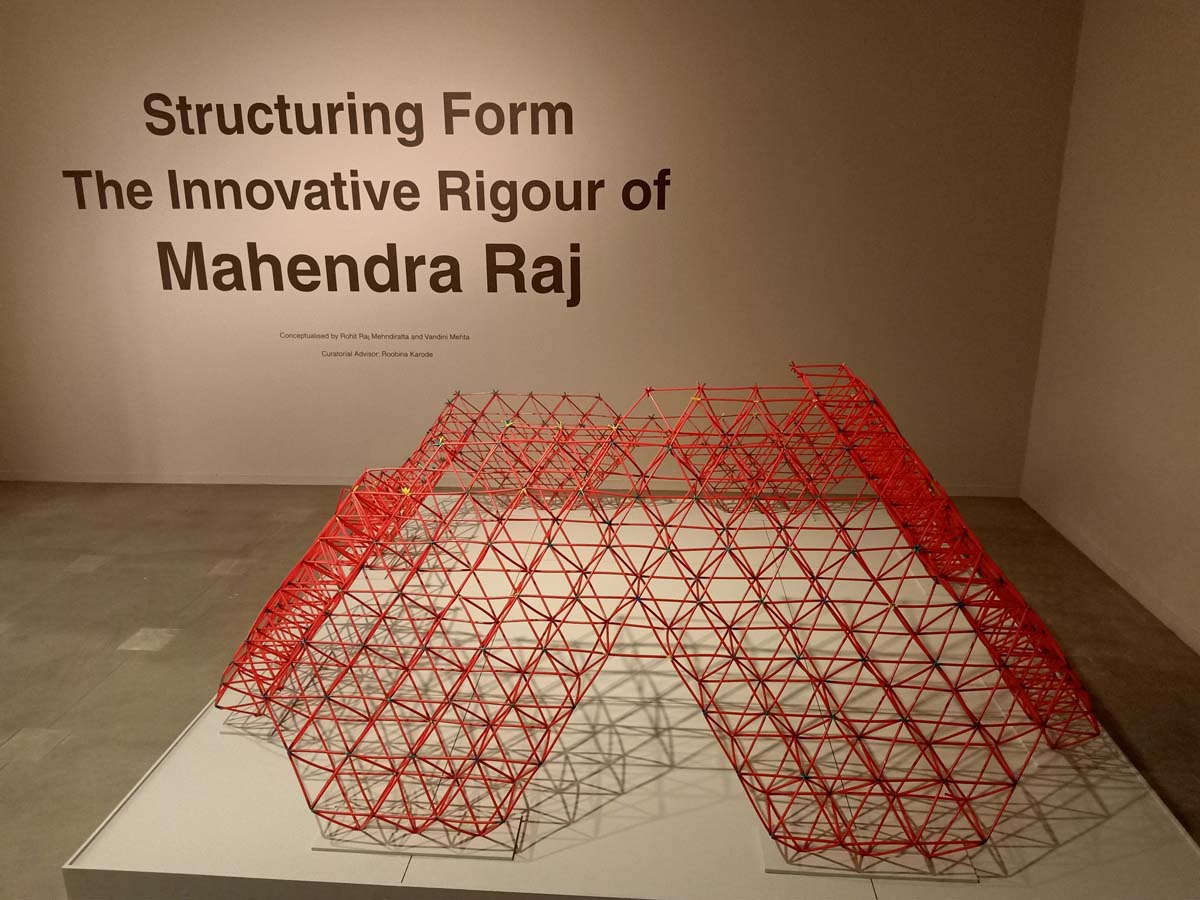

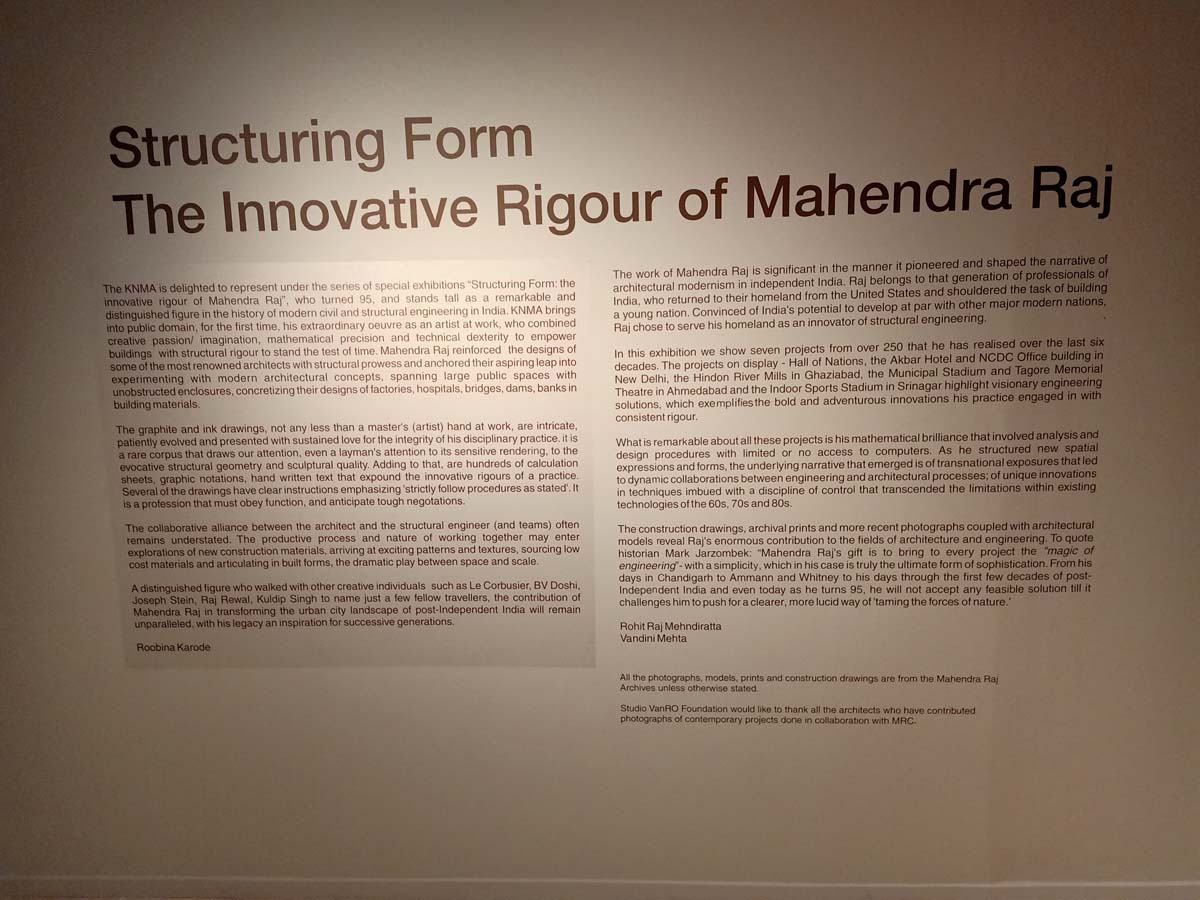

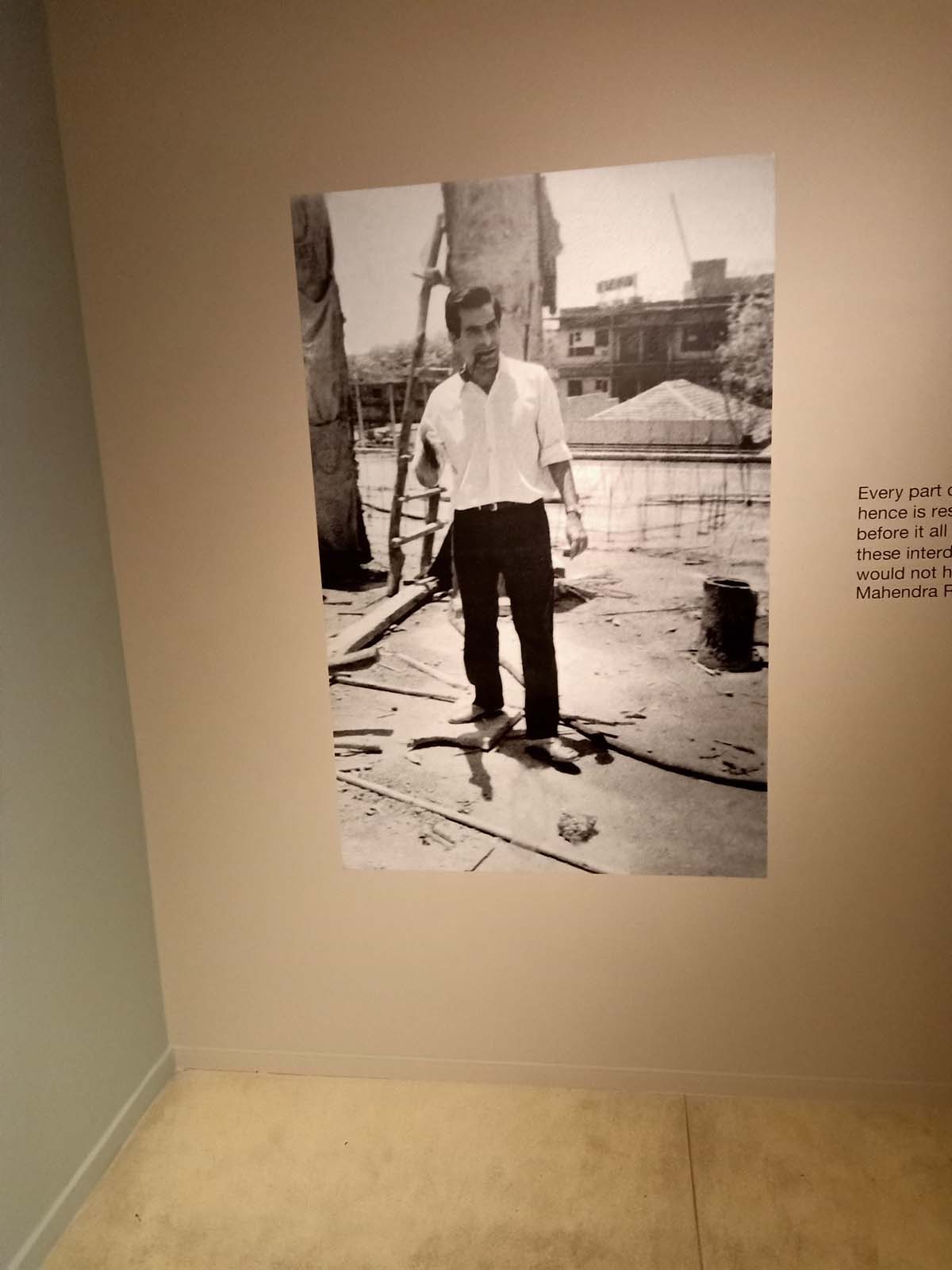

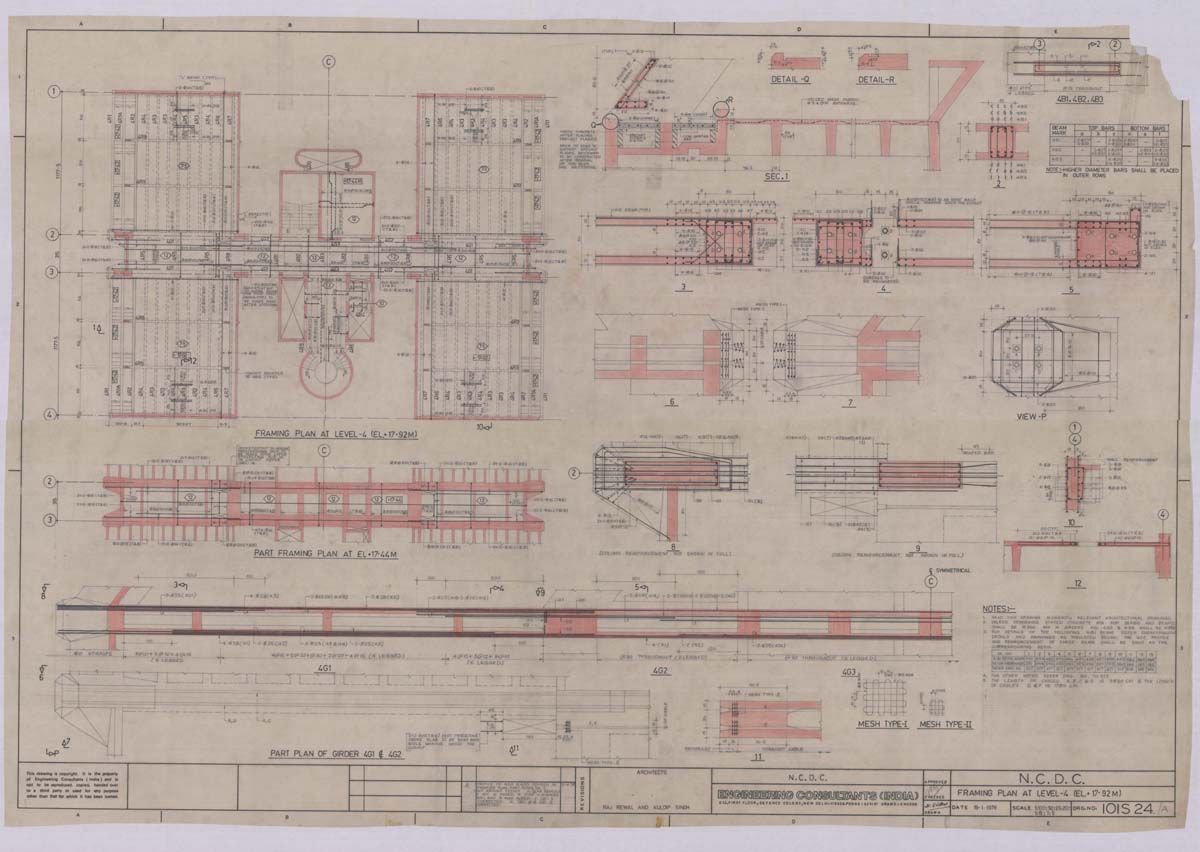

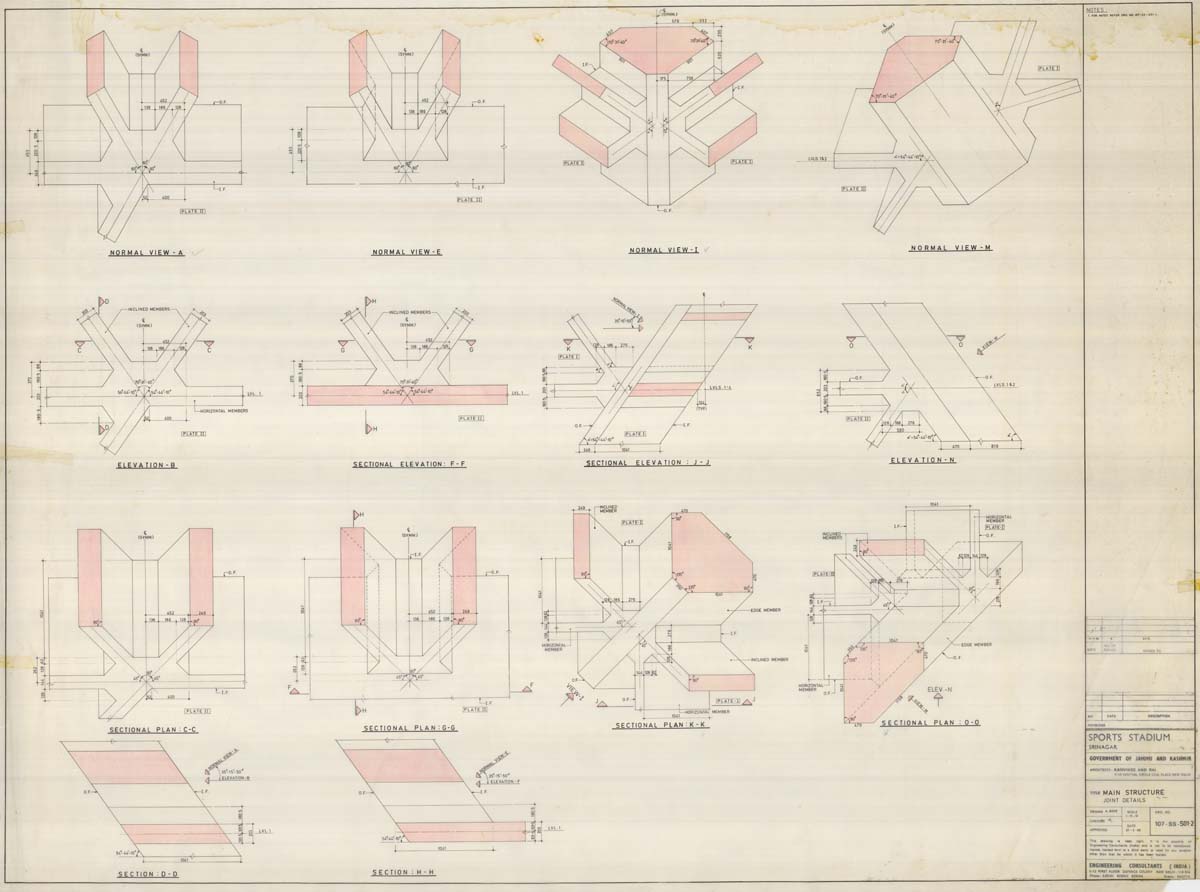

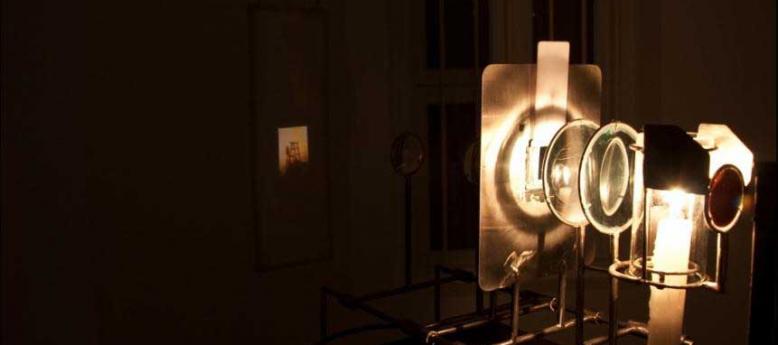

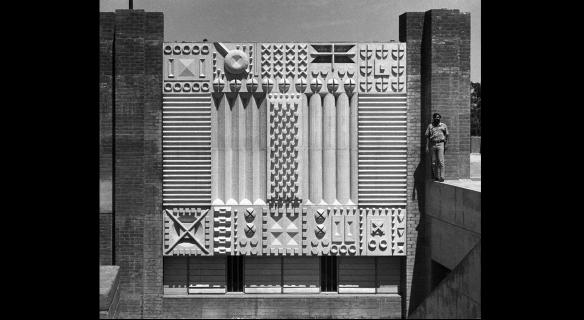

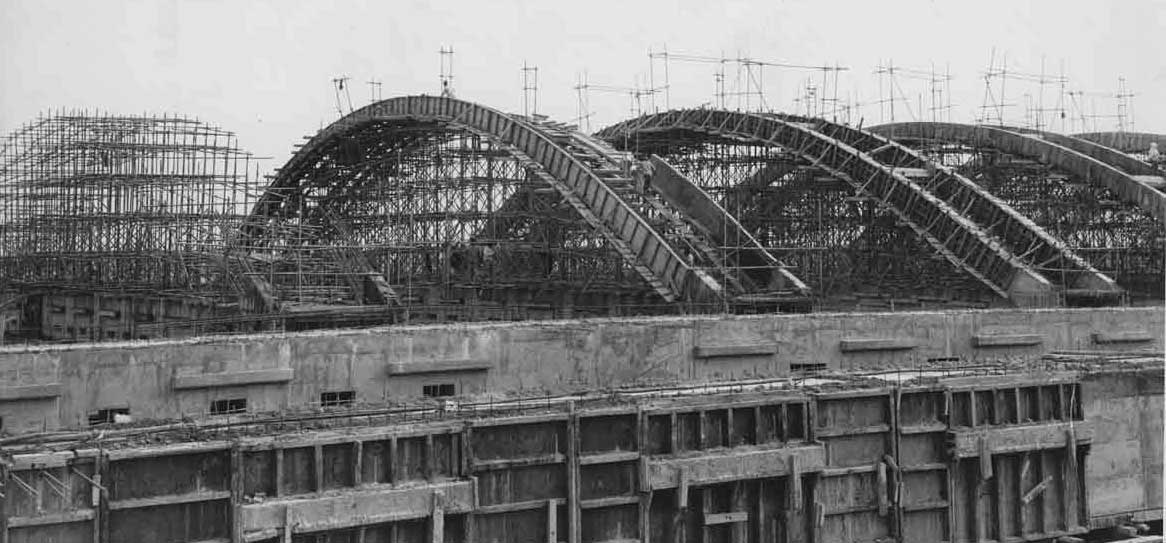

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art is pleased to announce a special exhibition detailing seven architectural projects, raised by the structural engineering genius of Mahendra Raj out of his two hundred fifty projects. The collaborative alliance between the architect and the structural engineer (and teams) often remains understated. The productive process and nature of working together may enter explorations of new construction materials, arriving at exciting patterns and textures, sourcing low cost materials and articulating in built forms, the dramatic play between space and scale.

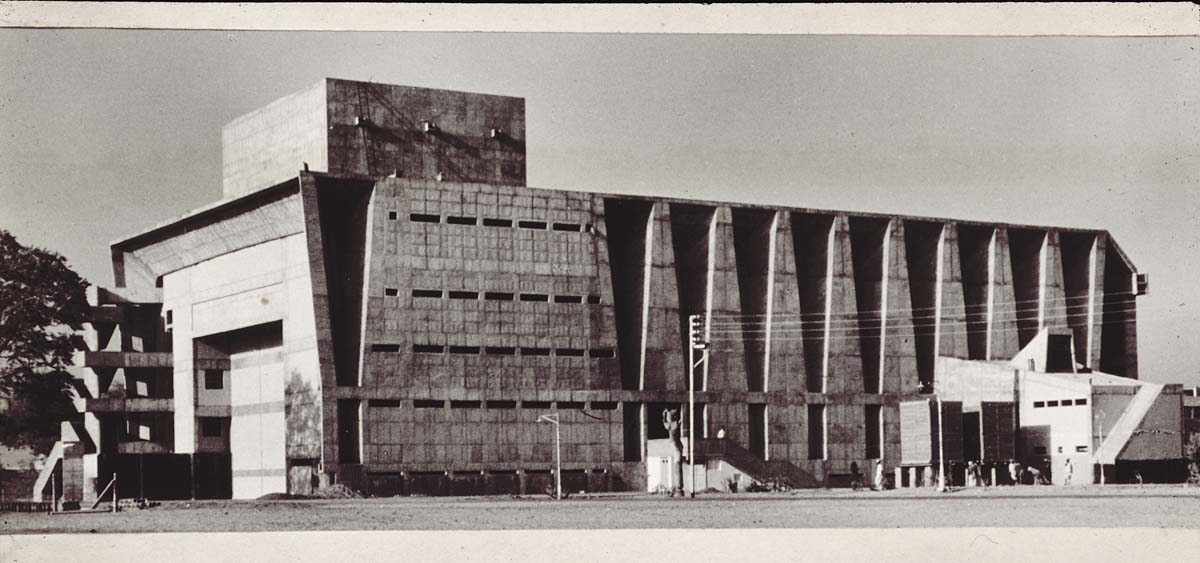

The projects like the Hall of Nation in New Delhi, the Akbar Hotel and NCDC Office building in New Delhi, the Hindon River Mills in Ghaziabad the Municipal Stadium and Tagore Memorial Theatre in Ahmedabad and the Indoor Sports Stadium in Srinagar find special place in this exhibition, alongside chronicling the career of this engineering innovator.

Architects like Charles Correa (Municipal Stadium, Ahmedabad), Raj Rewal ( Hall of Nation), BV Doshi ( Tagore Memorial Hall), Kuldeep Singh (NCDC Building) are considered hallmarks of modern India architecture. It was arguably their partnership with a Structural Engineer like Mahendra Raj that phenomenal modernist architecture found space on the developing Indian terrain. Mahendra Raj’s career can be mapped altogether the period of India’s Post-independence modernisation, a period marked by massive constructions flourishing across the country, that eventually changed it’s urban landscape.

The ambition of a budding nation like India was marked by widespread building of structures like stadia, theatres, bridges, dams, factories, airports, hospitals, universities and banks. The first prime minister of Independent India Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru hailed modern industrial buildings as the new age temples of modern India. Throughout the several ups and downs witnessed by the Indian economy over the decades, the developmental work that entailed a nation’s infrastructure was distinguished by recruiting a resourceful, avant-garde pioneer like Mahendra Raj.

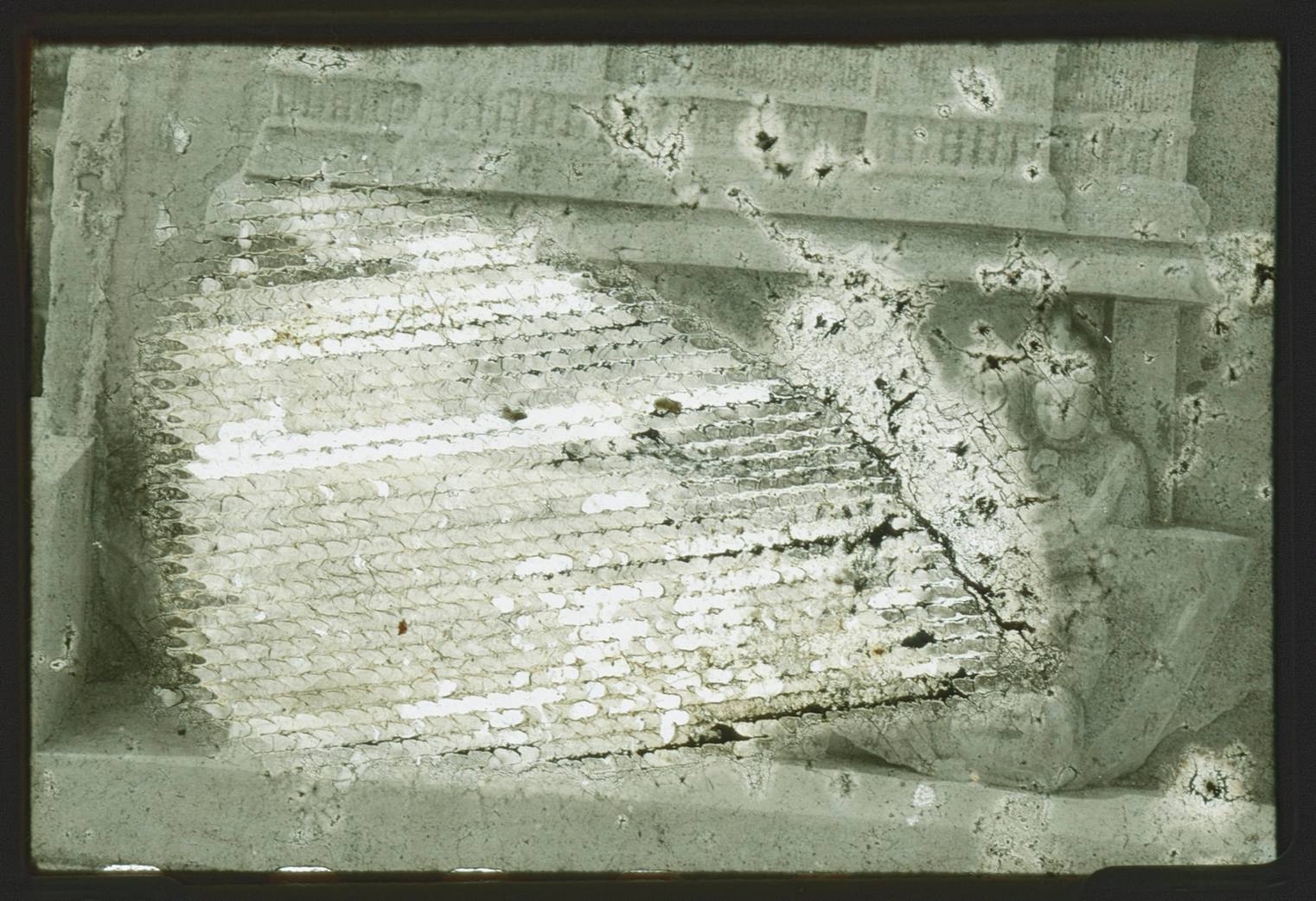

Concrete as building material was popular across the world, when Mahendra Raj executed these structures, however the material had its own limitations. In the 1960s, India was far from intense mechanisation unlike the western countries, Raj used this shortcoming to his advantage and experimented with structures, with the availability of affordable material and labour.

“Mahendra Raj has carried the whole modern Indian architecture on his shoulders. My interaction with him was like a jugalbandi that has helped enhance and execute my visions”, mentioned Raj Rewal[1], while describing the immense skill and tenacity with which Raj, executed these magnificent structures. Mahendra Raj’s ingenuity lay in the fact that he deployed easily available manual labour as well as construction material to craft his structures almost like artefacts, so unique that they went on to become his signature aesthetics.

His life and work garners much more relevance and attention in present times with the growing threat of demolition of modern structures like the iconic Hall of Nations, one of the featured projects in the exhibition, was razed to dust in 2017. The archive of his structures along with recent photographs indicate the power and elegance of different structures as they were constructed and laying bare the engineering inventiveness of Mahendra Raj. The drawings, especially the blueprints reveal the ‘techne’ of construction in different decades of Raj’s practice. These buildings were iconic objects, many with a commanding presence and setting, compelling one to look upon him as a craftsperson, even artist-visionary of his times and after.

[1] From the book ‘The Structure, Works of Mahendra Raj’, 2016, edited by Vandini Mehta, Rohit Raj Mehndiratta and Ariel Huber.

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art is pleased to present its first series of small exhibitions ‘Young Artists of Our Times’ curated by Akansha Rastogi, Senior Curator, Exhibitions and Programs. The series of exhibitions will unfold from September 2019 to March 2020, exploring different artistries, forms of attentiveness, indulgences and ‘transformational energies’ of youthfulness as a place, which is restless yet lazy, ‘too slow and too fast’, ‘rigorous and uninterested’.

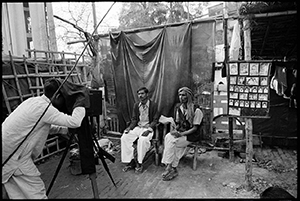

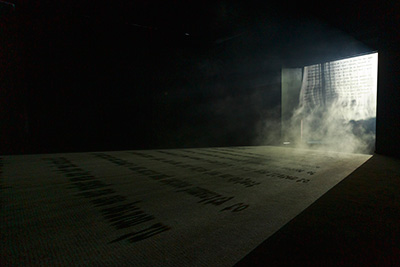

KNMA commissioned artistic research and project ‘Smells of the City: Scents, Stench and Stink’ by Ishita Dey and Mohammad. Sayeed in 2018 as part of ideation and thinking around museum and the city and urban ecology. ‘Smell Assembly’ thinks through Dey and Sayeed’s year-long project, and brings together walks, collections and annotations of smells from three sites in the city: Majnu ka Tila, fish markets of Chittaranjan Park, ittr shops and spice market of Old Delhi. The exhibition follows trails of smell-work of Sakha cab drivers, Shahri Mahila Kamgar Union, sanitation workers, smell-workers of Gadodia market, manual scavengers, ittr makers and associated clusters.

According to curator Akansha Rastogi, “Smell Assembly opens an anthropologist’s field diary in a contemporary art museum. It puts into focus the sensorial body as well as a researcher’s body purposefully wandering in the city, a body that maps as well as carries smell, as Ishita Dey and Mohammad Sayeed attempt a phraseology or elaborate on the structure of smells and their naming. The exhibition introduces a parcha from a fictional smell-workers union that re-imagines smell as the primary basis of reorganizing work and rate cards, and further invites to play and find one’s own temporary disposition or mizaaj through a smell game. Each collected smell translates into a micro-site with this spatial thinking and processing of research in an exhibitionary form, multiplying or displacing the primary sites of research and transporting viewers to various landscapes and memory-scapes through olfactory experience.”

Ishita Dey and Mohd. Sayeed’s Note:

“Smells surround us. Sometimes we can recognize one from the other. But mostly we can’t. A little subtle and they are ignored altogether. A little louder and they become intimidating. People have their own smells. So do houses. Streets too. And the cities, cities are known by their smells – different for different areas and changing with the time of the day and even seasons. But, how much do we know about smells. Do we have enough words to talk about them? Surely we can distinguish some by their names. But most we know through some or other associations. Smell of this or smell of that. As if cultures never thought of having dedicated words for distinct smells. Smells are intimate. They are like whispers, hence the emphasis on subtlety. To let a smell go wild is to shout out a secret in public.

When we know the smells through their associations, often they are material things. We can smell fear. To be at home in a city is to be surrounded by reassuring smells. Can smells express the abstract sense better, giving it a material touch, or whenever we speak of smells we are always speaking of the figurative?

Smells help us to navigate through nooks and corners of every city and Delhi is no different. One of the challenges that city’s planners face is to keep the city smell free. In this context it would be important to remember Delhi’s tryst with closure of industrial units, shift from diesel and petrol run automobiles to compressed natural gas or constant debates on the ever increasing height of city’s landfills. Amidst these debates, what is missing is how smells are felt, expressed through human – non-human interaction.

There are two related questions that we want to explore. First one relates to the representation of smell. If one cannot record a moment of smell, to come back to later or, let’s say to share it with a friend, what are the ways, through which, we remember them or recognize them? Is it possible to translate smells in other mediums–visual, aural, language–in order to understand to what extent the smells have a bearing on contemporary urban life. How do smells represent the metaphorical sense of being in the city and how smells themselves can be represented in search of what is hidden from visual and aural grasp of the city. Secondly, how would an olfactory map of the city look like and how does it express the social? Can social relations be expressed in terms of control over one’s own and surrounding smells? Who has the control over its perpetuation and expression, and who has to live with it and under what condition. How do urban dwellers navigate the inescapable olfactory map of the city?”

The exhibition over the edge, crossing the line: five artists from Bengal continues its showcasing at Saket, after opening early January at the Noida branch of the museum.

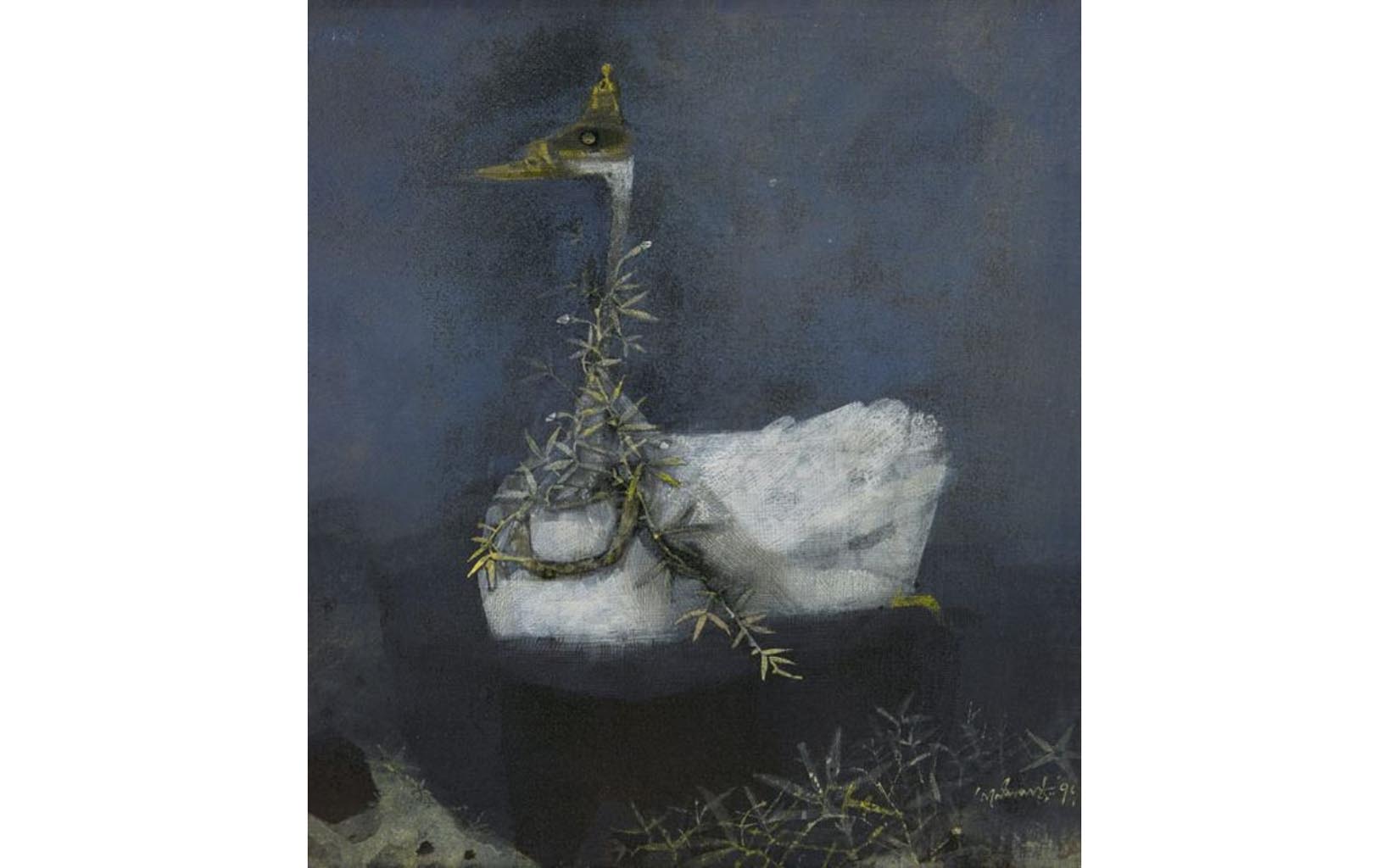

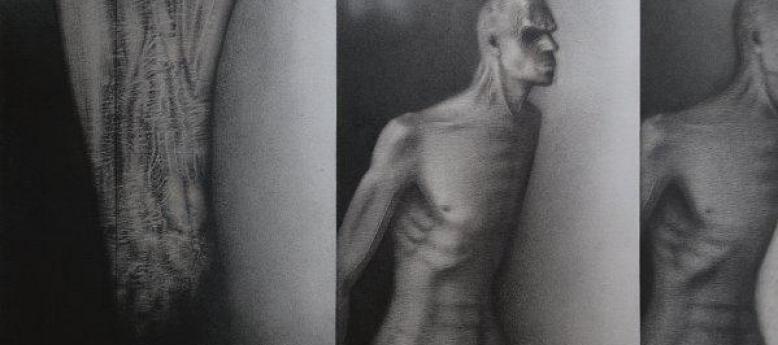

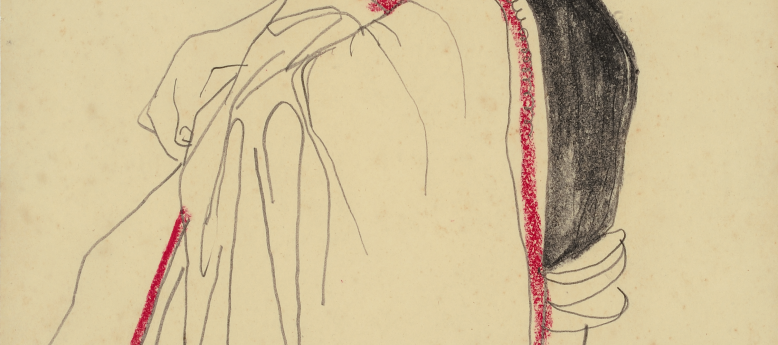

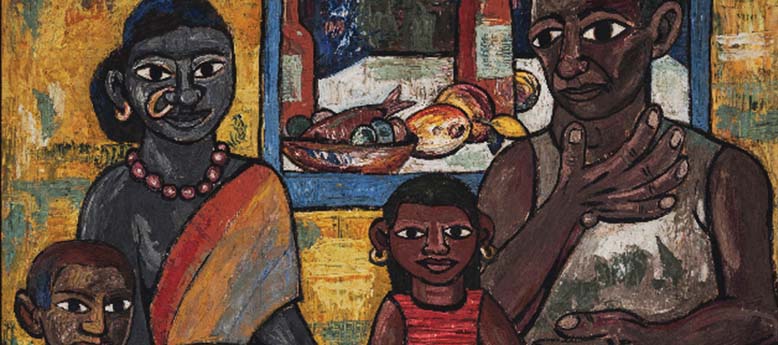

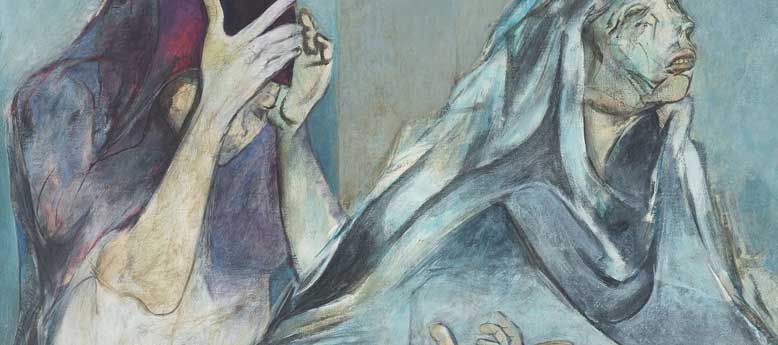

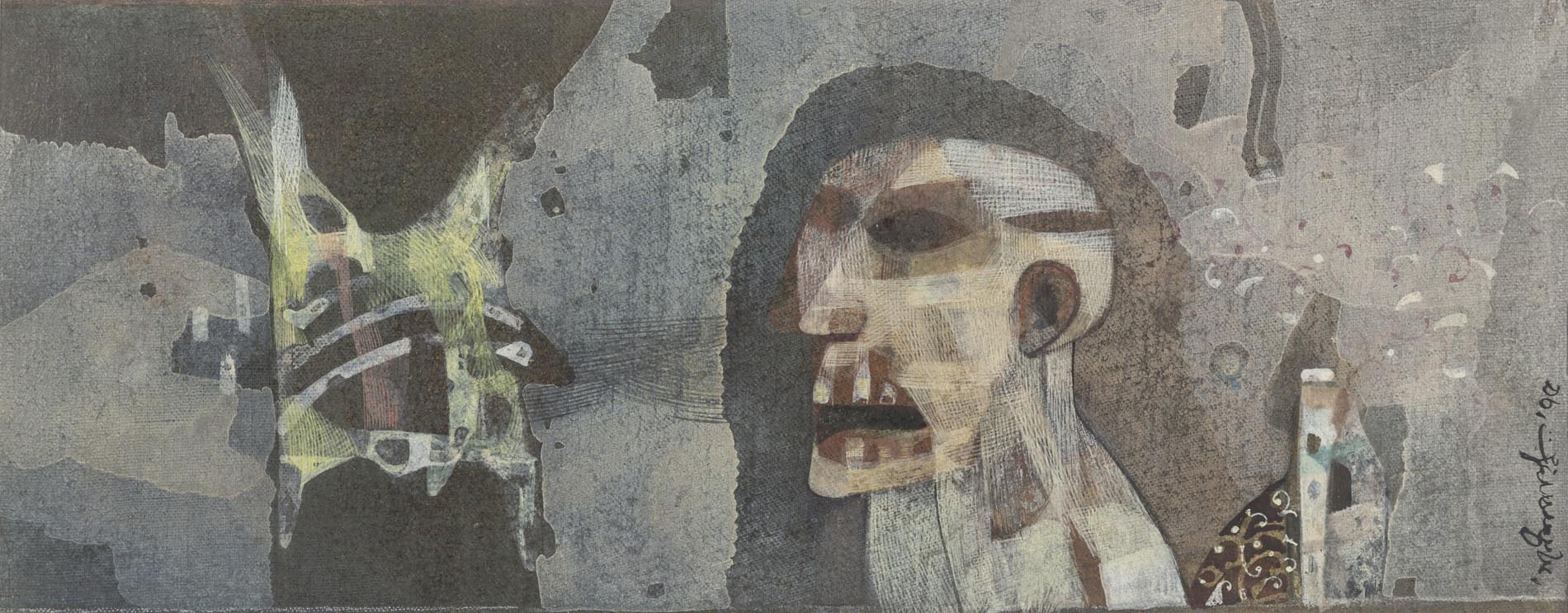

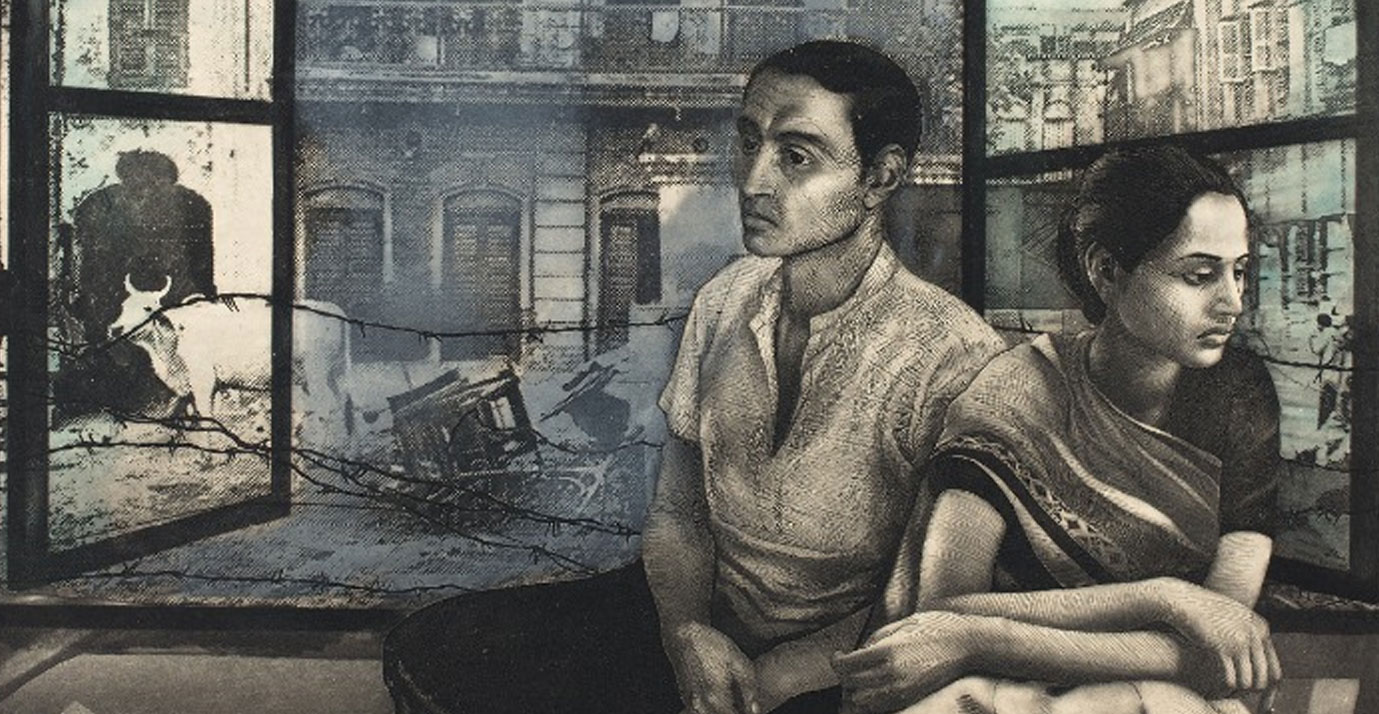

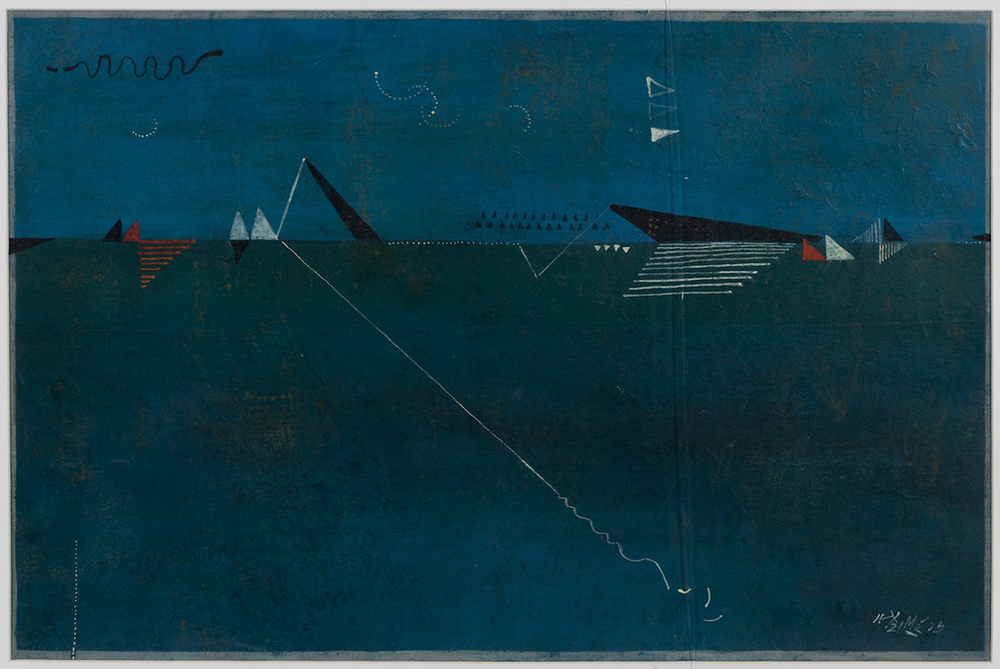

Continuing the extensive explorations of different art movements, regions and artistic ideologies within South Asia, this year KNMA presents in-depth oeuvres and artistic inclinations of five modern masters from Bengal: Ganesh Pyne (1937 -2013), Meera Mukherjee (1928 – 1998), Somnath Hore (1921 -2006), Ganesh Haloi (b.1936) and Jogen Chowdhury (b. 1939). Coming from various parts of Bengal, their visual vocabularies reach maturity during 1970s and 1980s, with the city of Calcutta emerging as an intersection point. The social and political changes, witnessing and observing major occurrences like the Bengal famine, the Tebhaga movement, the Bangladesh Language Movement, the Vietnam War, and avant-garde mobilization in the creative disciplines of literature, cinema and theatre, has shaped their individual artistic styles and preoccupations. The chronological radius of the exhibition spans more than five decades from 1960s to early 2000s, showcasing more than two hundred artworks from KNMA collection and loans from artists and private collections.

The exhibition pursues the intensity and the edge at which these five practices seem to be located. It tries to look through the traces of what has remained or distilled through long duree process of artistic gesticulations on canvas or paper. Delving into the empirical and the subconscious, these five modern masters have created extraordinary visuals, meticulously ossified from the worlds seen and sensed. They take viewers on a journey to the unknown, and speak of both, longing and suffering, sometimes through direct representation of the real, and at times with allegories and obscure symbols. The exhibition oscillates between scenes soaked in half-light, colour fields, unbroken lines or contours of a figure, decay and poetic distortions, as if almost hiding the corporeal body and paving paths to view the body of a landscape.

Collective anxieties and turmoil surface often in interesting ways in this selected body of work. The exhibition explores how the transfigured, charged and complex imagery challenges rigid perceptions of viewing. With approximately thirty to forty artworks of each artist, the exhibition takes one through their unique journey from different phases of aesthetic formulations: from being chroniclers, appropriating the roles of narrator, illustrator, image makers and activists to being myth-shapers. A diverse range of techniques, mediums and configurations: paintings in tempera, gouache, watercolours, mixed media, ink and pastels, woodcut, lithography, etching and paper pulp prints and sculptures casted in bronze and plaster of Paris constitute this presentation.

For instance, Ganesh Haloi’s untitled gouache works punctuated with sporadic yet minimal colour patches and hyphenated lines, transport the viewer to imaginary pasturelands. These transitory landscapes hold the memory of real pathways and evoke a sensory and spatial experience of movement. In an almost contrasting rhythm are Ganesh Pyne’s quick jottings in pen and the multi-layered tempera works like Death (1975) or The Swim which falls between the real and the mysterious. Pyne, who has always been immensely drawn to water, creates these layers of dark undercoats of paint and then applies lighter colours to create mysterious effects, invites us to take detours from the surfatial. Meera Mukherjee’s sculptural explorations of myths and decorative patterns, modelled with a certain solidity of wax, recreate her observations and learnings in bronze-casts techniques learnt from living with the craftsmen of Bastar. Her sculptures like Nagardola (Ferris wheel) or Srishtidepict the cyclical rhythm of human survival.

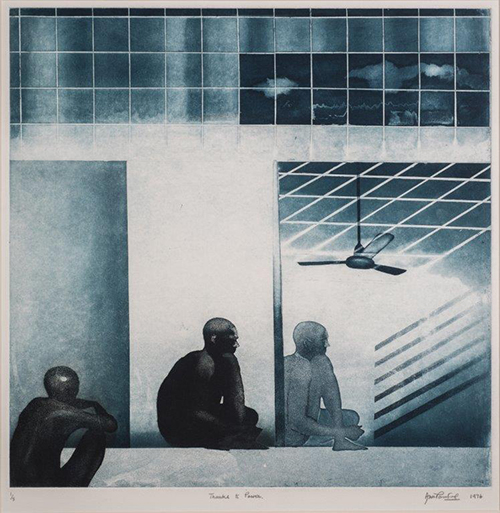

In Jogen Chowdhury’s Gulabi Takia (1977-80) made in ink and pastel on board, or A Couple (1984) painted in ink and pastel on paper, one sees the tender or uneven contours of human figures made with intricate crosshatchings. They lack firmness as if mirroring the deformation of societal structures. Somnath Hore’s figures, studies and symbolic open wounds tend towards minimal forms. He pulls our attention to the emaciated bodies who are delicately etched between hunger and fasting. His Wounds (1973), the paper pulp prints, though echo the memories of violence in Vietnam war, are reflections on human existence and the sufferings from man-made wars and scarcities.

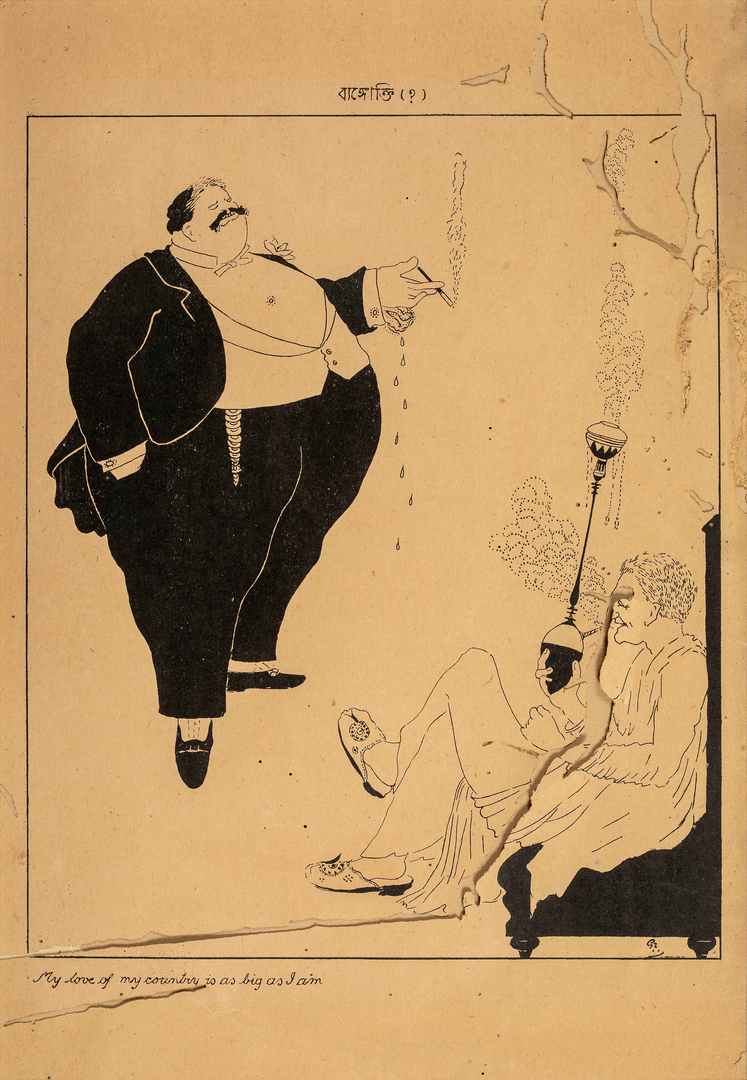

Poetic, satirical and political commentaries of

Gaganendranath Tagore, Chittoprasad, KG Subramanyan and RK Laxman

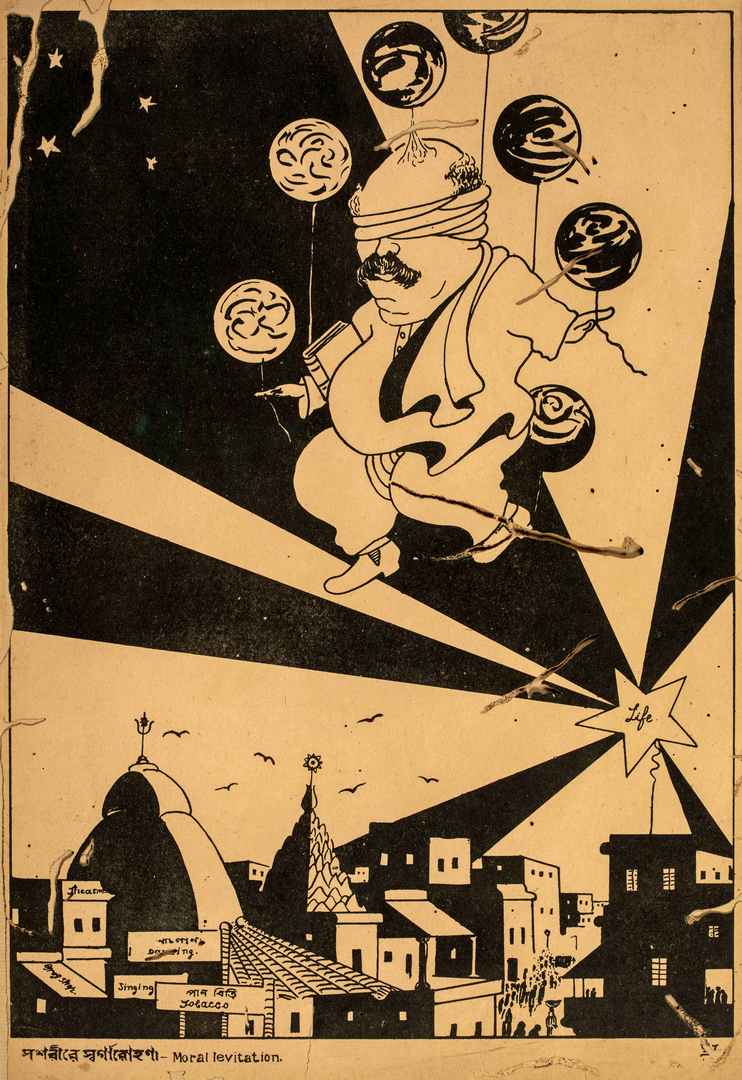

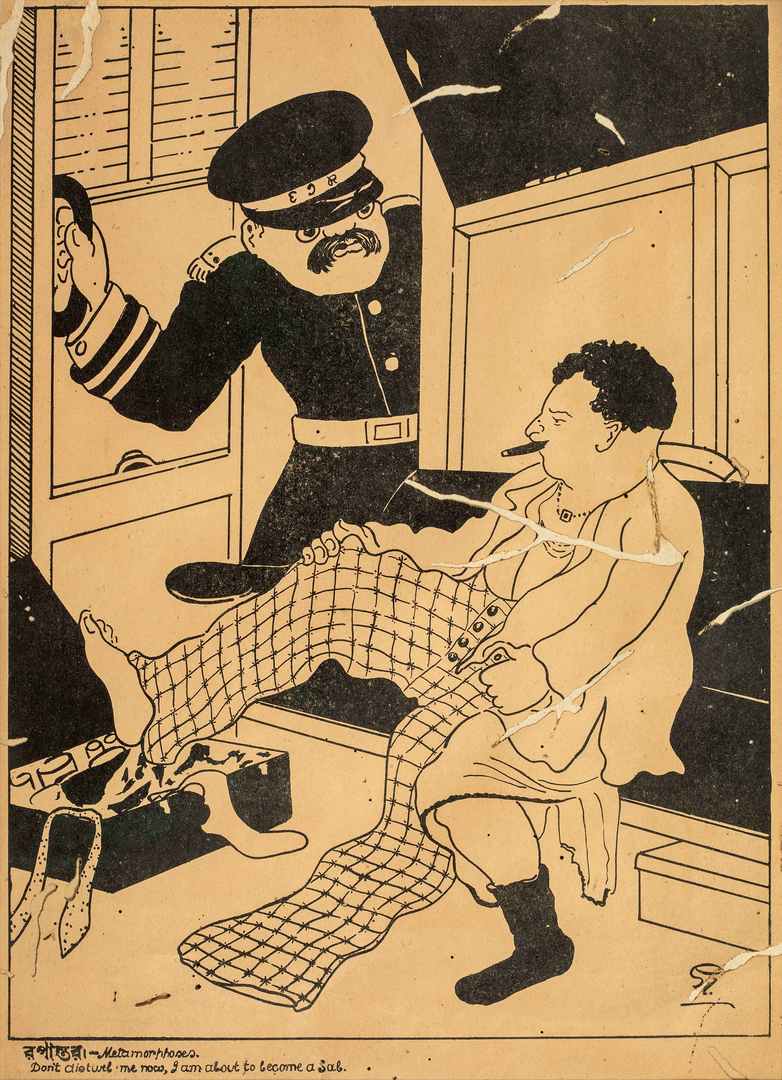

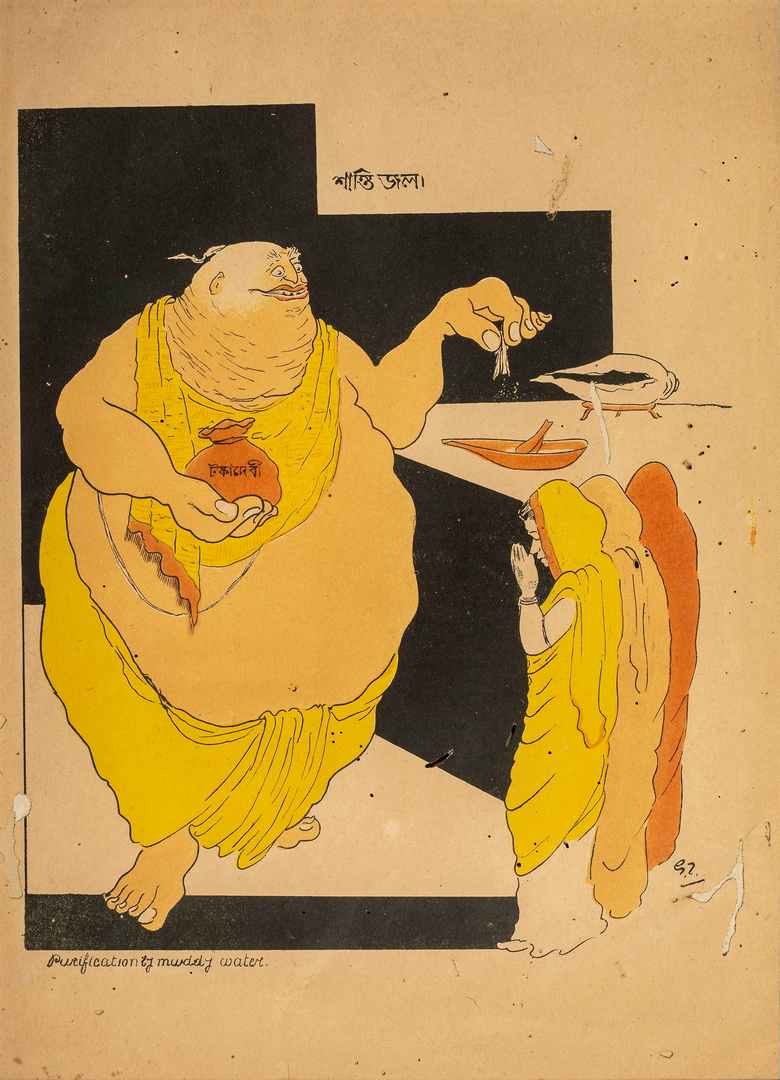

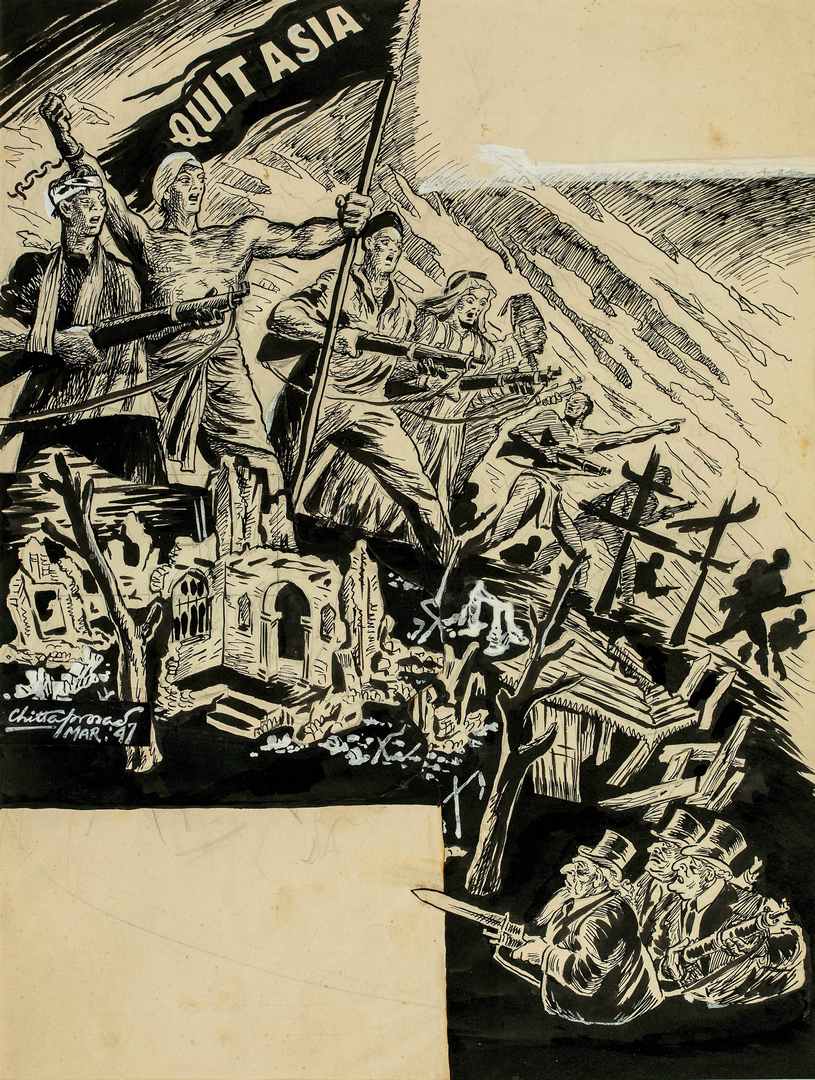

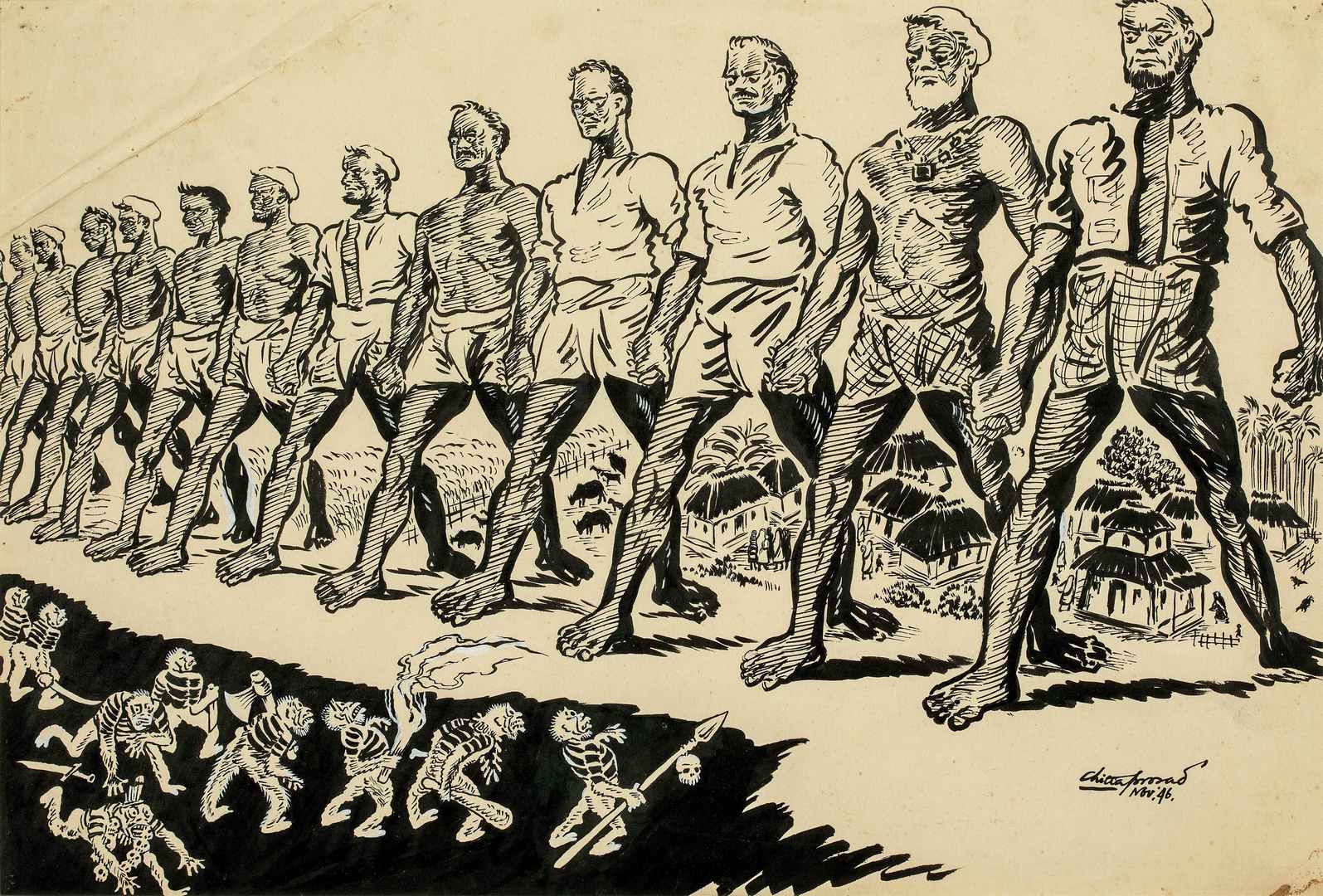

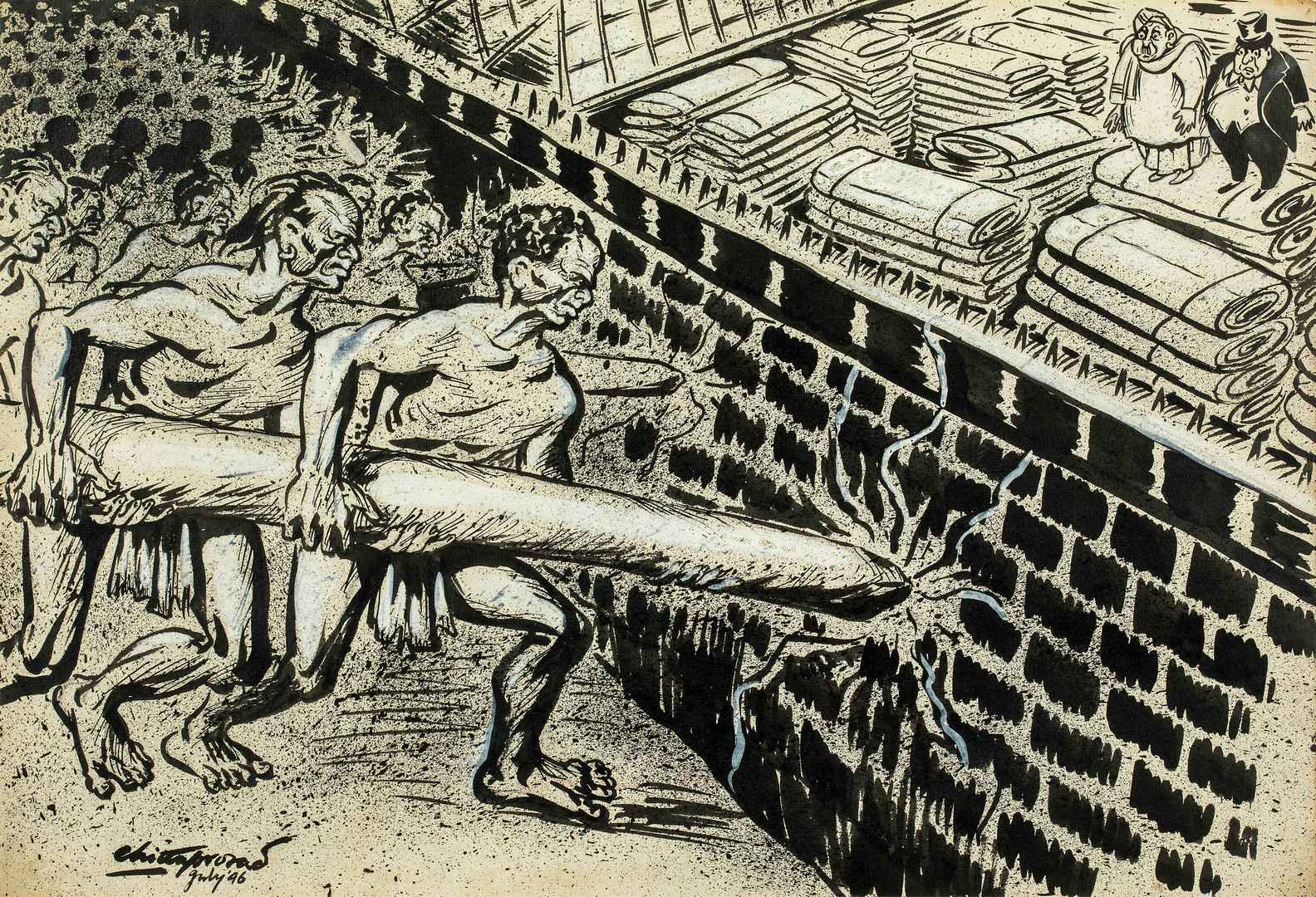

‘Common Course’ is a zestful and humorous ride through caricatures, satirical, poetic and political commentaries of four artists of modern India. The exhibition brings forth the stereotypes, contradictory/ critical impressions, resistance, bold alerting signals to civic and political consciousness and moral crises of colonial India as marked in the political posters of Chittaprosad and commentaries of Gaganendranath Tagore on the topical and social history of Bengal. These along with KG Subramanyan’s incisive and stinging poetics on the political drama that unfolded during the 1970s Emergency period and the recurring character of the common man in RK Laxman’s cartoons, interprets and voices opinions on political events and the politics of everyday in post-independent democratic India.

The exhibition includes original lithographs and collaged pages of two seminal books. First one is Gaganendranath Tagore’s album of caricatures ‘Adbhuta Loka (Realm of the Absurd) made in 1917, which captures the strange deformities, social negotiations and transformations happening in colonial city of Calcutta. He draws on the urban stereotypes of the babus, priest, aristocrats, and anglicized bhadralok that he called as ‘hybrid Bengalis’ who are represented in his works as young men half-clad in Indian dhoti and half in European dress. In the introduction to his another album ‘Virupa Vajra/ The Wry Bolt: Play of opposites’ he wrote, “When deformities grow unchecked but are cherished by blind habit, it becomes the duty of the artist to show that they are ugly and vulgar and therefore abnormal." The second book is ‘The Tale of the Talking Face’ by KG Subramanyan. The original collages not only give an insight into the workings and artistry of the master-storyteller and pedagogue Subramanyan, but also the satiric verses that lead us onto the threat of totalitarianism looming through the autocratic ruler/protagonist of his tale. Published in 1989 by Seagull, KG Subramanyan started work on the series in around 1975 when India was under the emergency rule. An array of 43 paper collages constitute the template, building and holding the tension through the black and white spatial registers of events layered with multiple focal points of the narrative.

Treading across varying nomenclatures and understanding of the role of an illustrator, graphic novelist, cartoonist and agitated political resistance, the exhibition reflects on the rich visual syntax and narratives rooted in the conflicts and contradictions of the respective times. It highlights the practice of chronicling social, political and cultural changes in the society through the myriad ways of telling a tale. ‘Common Course’ cuts across genres of popular prints and book illustrations, subverting, parodying, lampooning with characteristics of pictorial journalism, exaggerated physiognomies of protagonists, readings of the political ties and social tensions, common set of criteria or the rising collective effort of the oppressed. ‘Common course’ is a play on the assertion and rights of the commons.

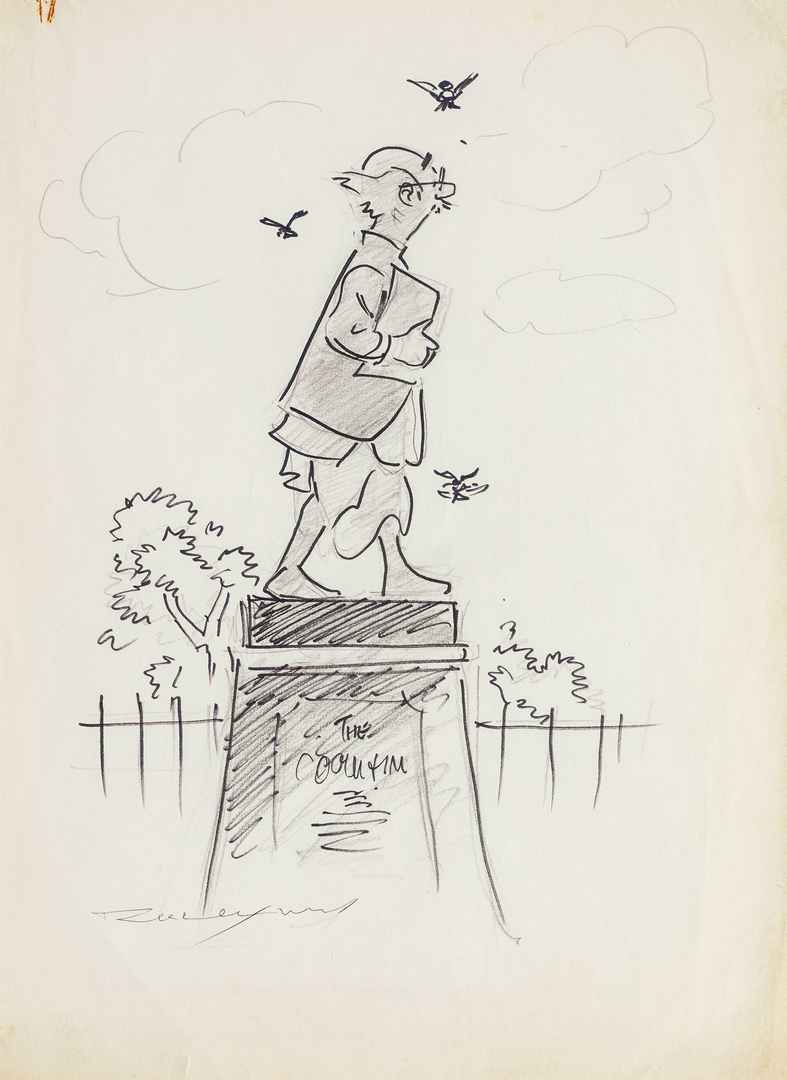

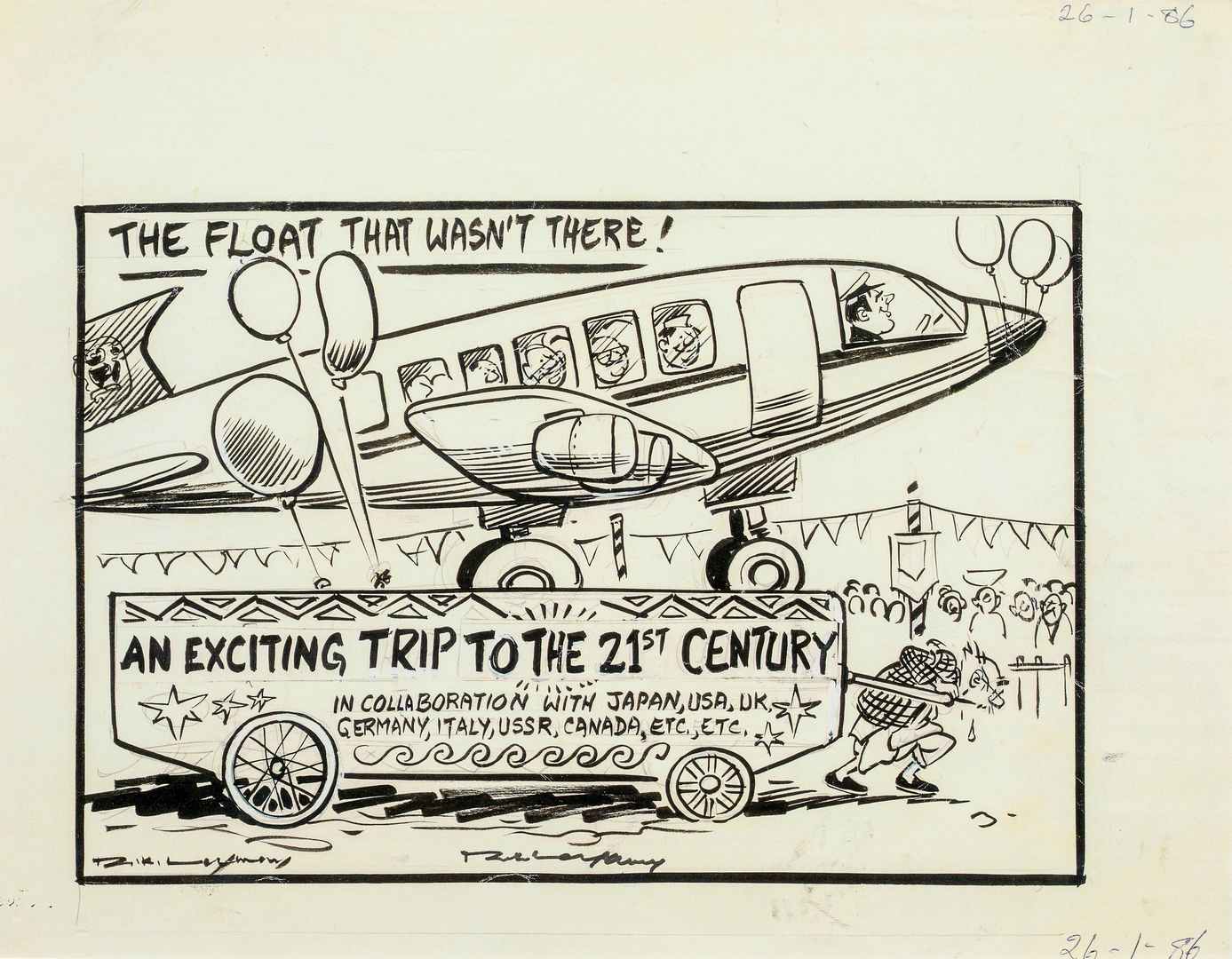

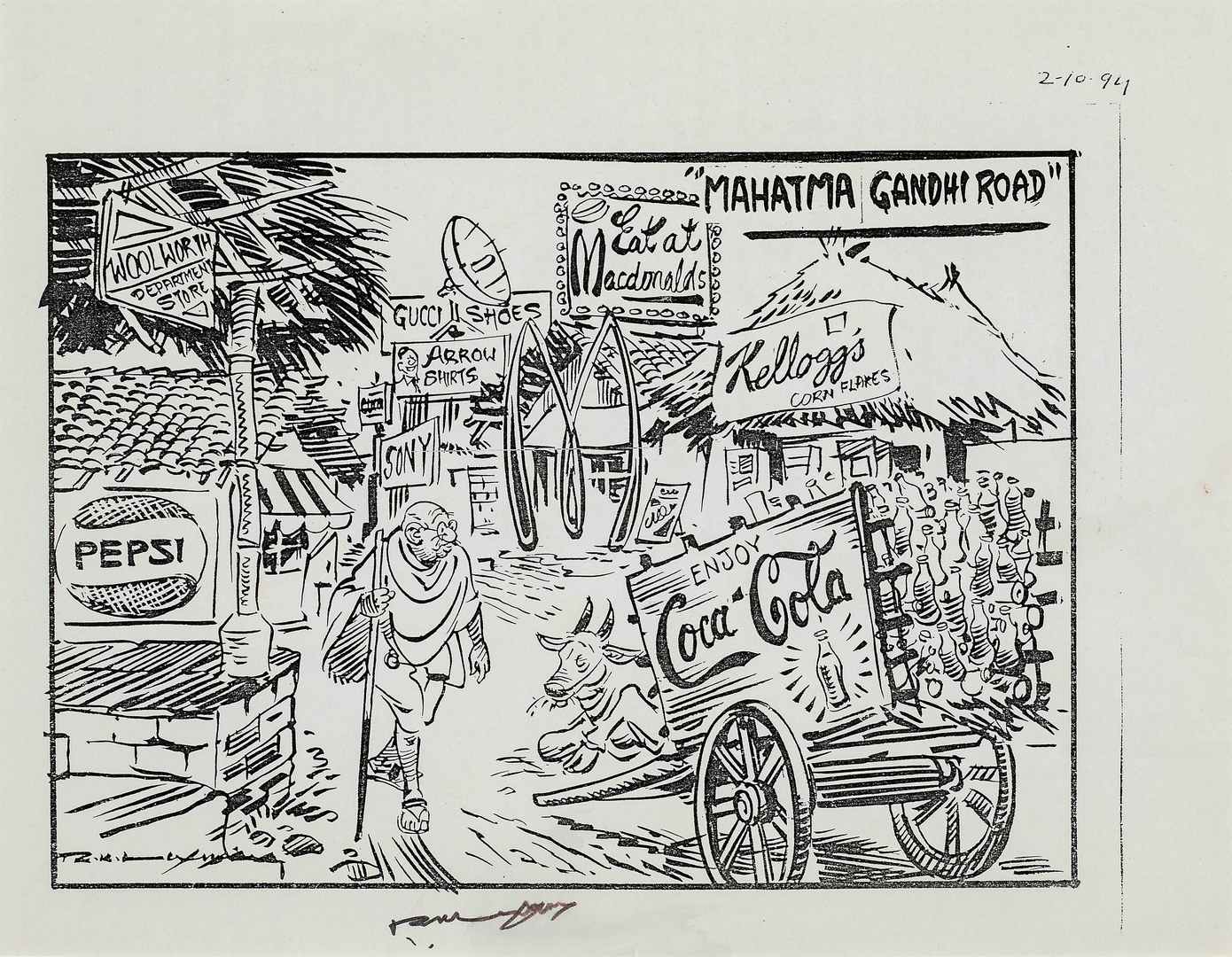

RK Laxman as an artist, could be hailed as the vidushak or jester of modern Indian Politics. The protagonist of his cartoons ‘the Common Man’ is a curiously omnipresent bespectacled middle-aged balding man in his modest dhoti and checkered coat, who silently witnesses the humdrum from a tiny corner of the front page of the daily newspaper. This quintessential ‘Common Man’ bears familiarity with anyone acquainted with the daily affairs of Indian nation. From the prolific oeuvre of RK Laxman, KNMA showcases a rare feat of cartoons where listening, observing, sharp analysis and political commentaries is performed on the most crucial events of the nation. When showcased as a tableau, the immediacy of his swift brush strokes and stinging nature of his humour while unrobing the follies of his peers is palpable. They take you on a tumultuous journey of a newly independent country, its various domestic and international vagaries, and hypocrisy of its leaders and the scandals from 1950s to 1980s. He caricatured almost all significant political leaders and popular public figures of his time, few of the iconic ones are part of the exhibition.

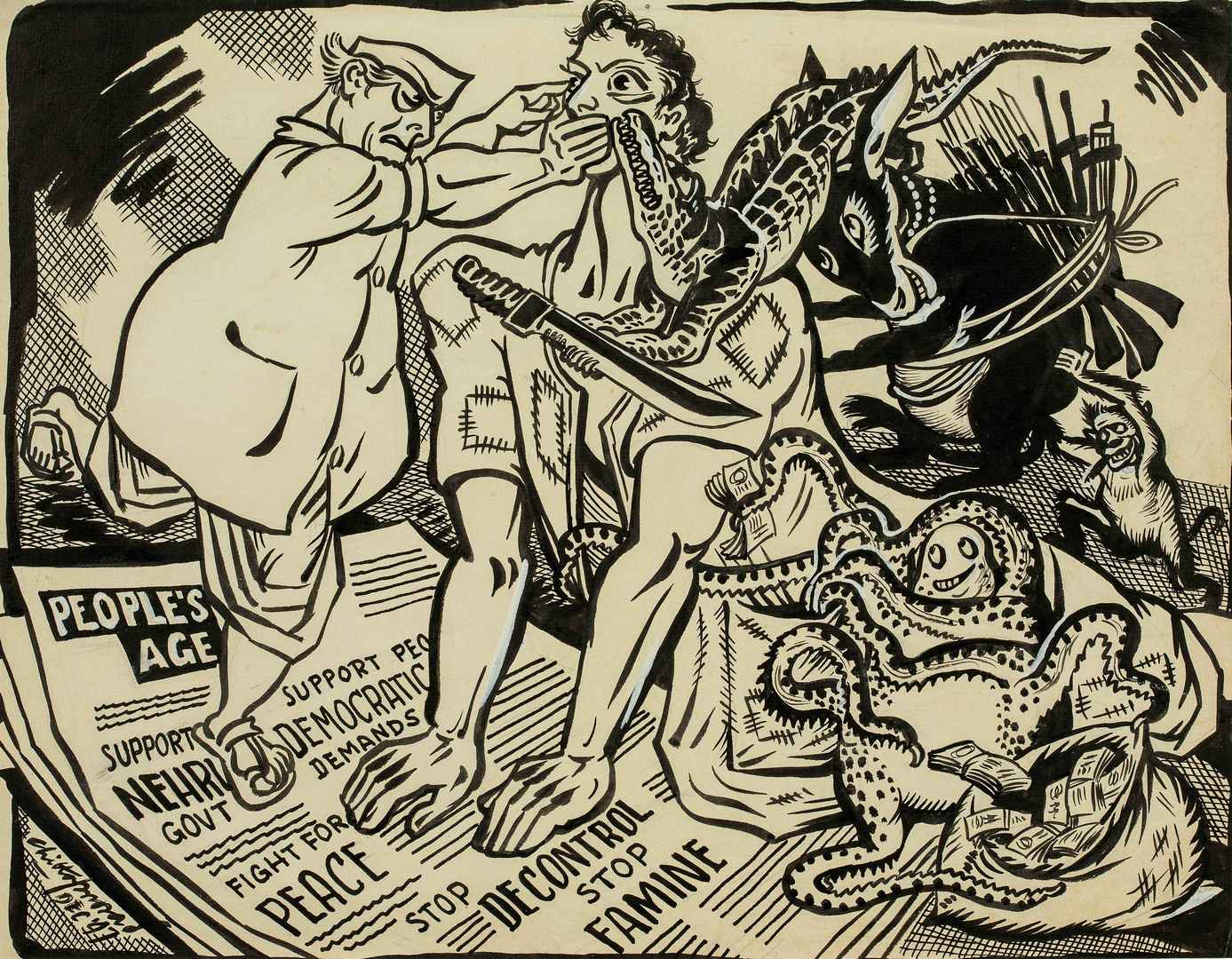

The intense pen and ink drawings and political posters of Chittaprasad from the 1940s and 1950s document and comment on both the world and national political scenarios. There is no meddling or double-speak with the ideologically charged political art of Chittaprasad, it cuts straight and hard just like a hammer and a sickle. He critiques imperialist domination, British India’s repressive policies, the unity of peasant and workers’ union in the face of the trinity of sarkar, sahukar and zamindar, the Royal Navy mutiny, the communal politics of partition, to the challenges, tyranny and social evils of post-independent India. Chittaprasad in his drawings demystifies the ‘politician-capitalist nexus’ manifesting as neo-liberal free trade propaganda to its bare bones of exploitation and growing rich-poor divide. Yet we see that somewhere there is a dream of a utopic future, comprised of peaceful and self-sustained villages with plenty food and work, unfurling under a hoisted communist flag. The regimes have changed, the role of Communist Party is debatable in times today, and the monsters of neo-liberal economy have grown beyond comprehension. Yet Chittaprosad’s artworks adhere to a recounting of the buried truths of a troubled history of India’s development, albeit drenched in ink and strokes of compelling figuration of the common citizen from the margins, upon whose aspirations it has pillared its growth on.

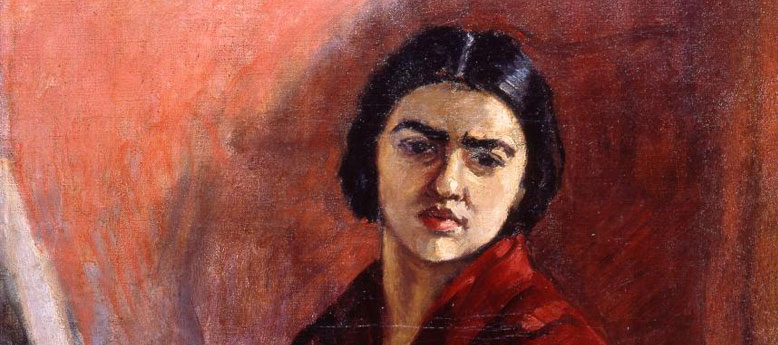

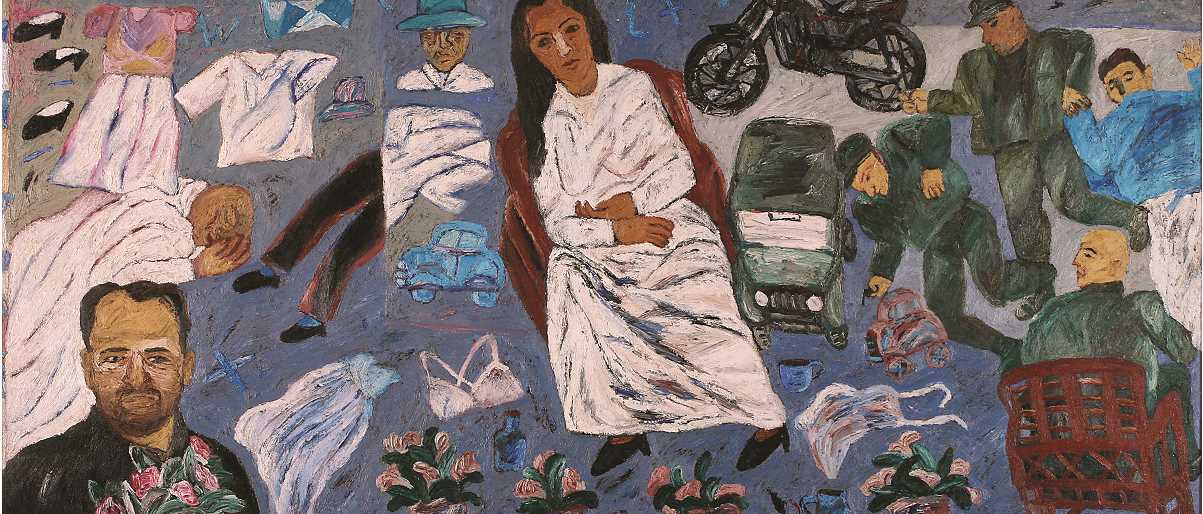

Arpita Singh (b. 1937, Kolkata) is one of the most significant women artists in India. This retrospective exhibition at KNMA gives an extraordinary opportunity to view six decades of her art practice. Engaging with her complex view of the world through her seminal paintings, drawings, sketches and watercolours from various public and private collections, the exhibition focuses on her long and singular commitment to the medium of painting and its evolution into a personal expressive language.

Artists: Sreejata Roy and Mrityunjay Chatterjee

With Hoor Kareemi, Fariba Azizi, Rabiya Taraki, Mari Saidi (Afghanistan); Aya Nazari (Iraq); Gloria Ntsoni Badidila (Republic of Congo); Safa Mutombo (Congo Democratic Republic); Sirie Senai, Jaana Berhane (Ethiopia); Ladan & Shuba (Somali); Dolly Singh (Bihar); Laxmi Chhetri, Radha Sharma (Nepal)

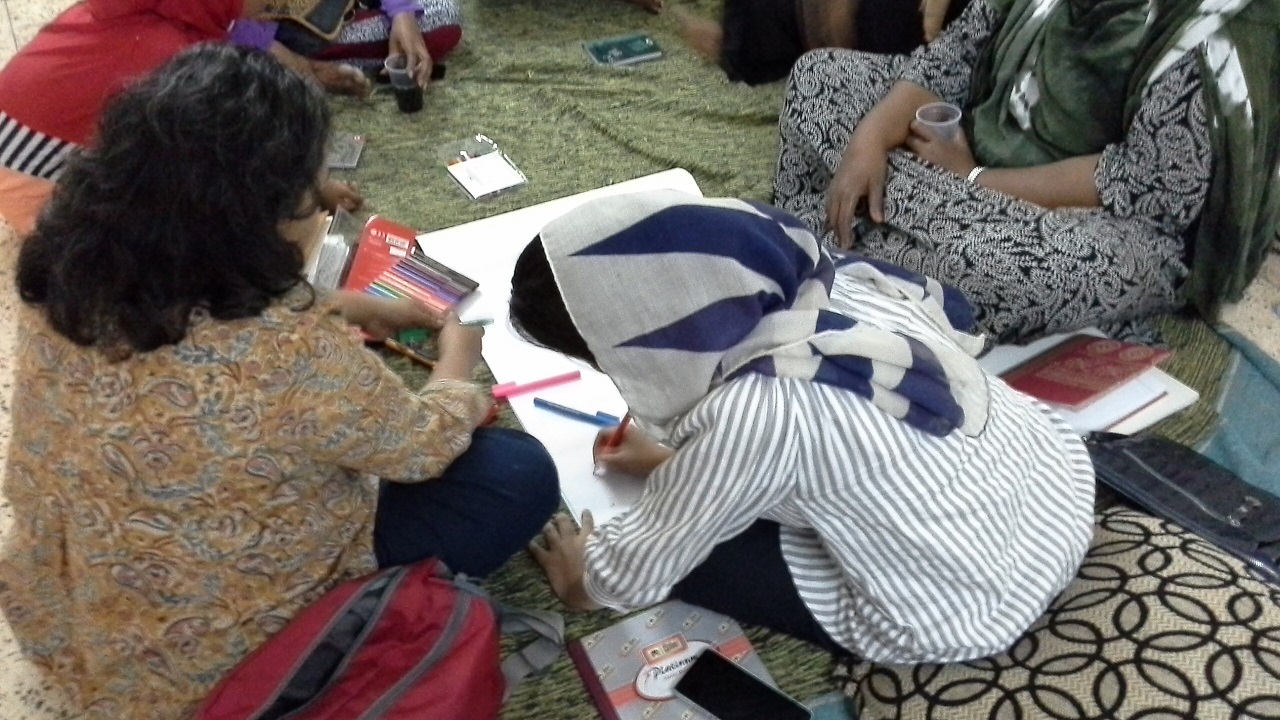

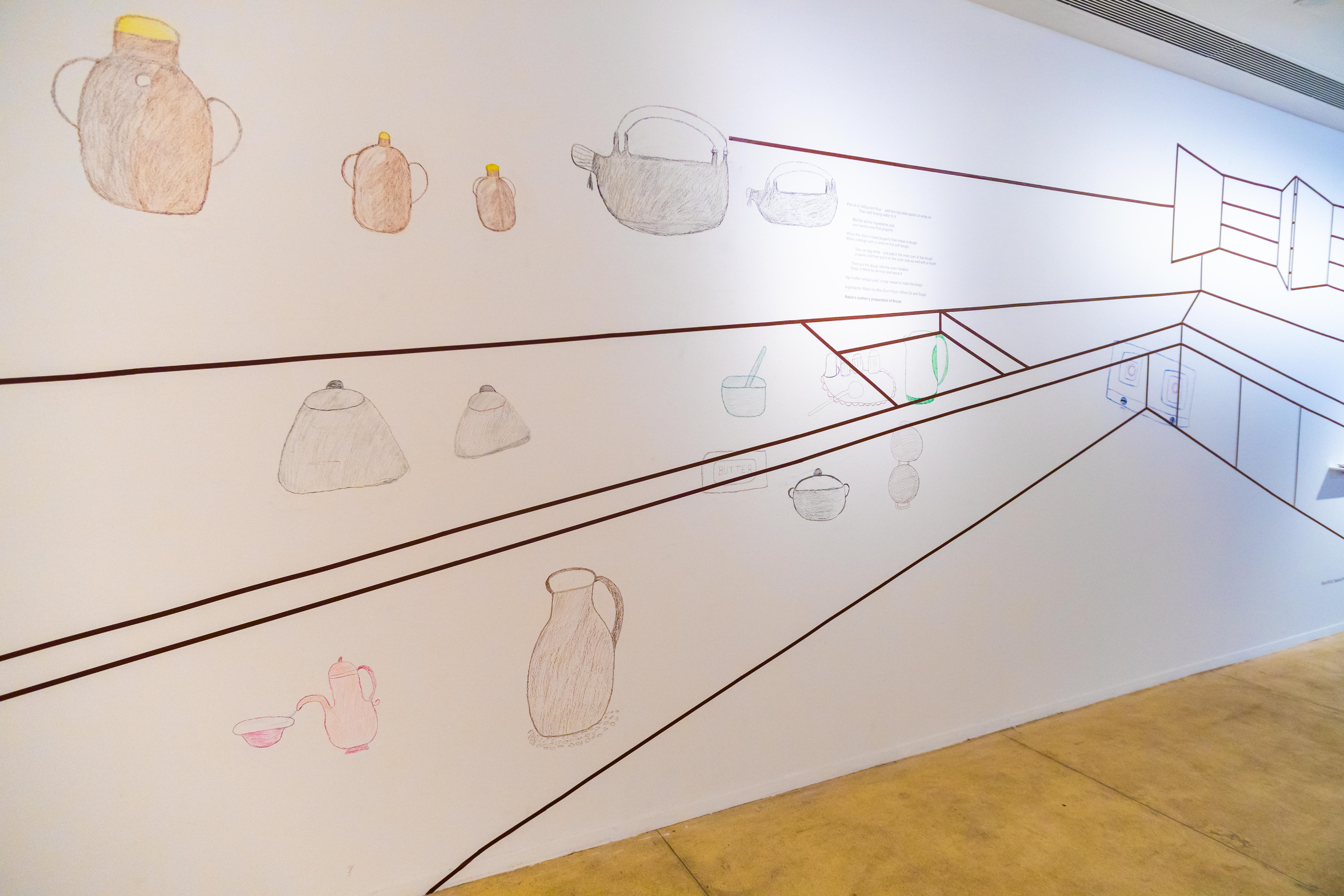

KNMA is pleased to present the exhibition ‘What Place is Kitchen? What Place Community?’ which completes a year-long project ‘The Khirki Living Lab’ by Revue (Sreejata Roy and Mrityunjay Chatterjee). The community kitchen in the Khirki Living Lab has connected migrant women from different geographies living in the neighbourhoods of Khirki and Hauz Rani in South Delhi. The project enabled a dynamic network of social relationships and friendships through the daily act of cooking a wide range of cuisines in a common kitchen, sharing recipes and eating together.

The exhibition begins with an outlining of the three kitchens/studios in Khirki Extension that the Living Lab inhabited by an amorphous group of migrant women (along with their children) from the Middle-east, different countries in Africa and Asia, who met regularly, cooked over ninety-three recipes and conversed over meals. And slowly it reassembles the processual that occurred over a period of one year: the list of around ninety-three dishes, different songs and conversations, glossaries of foodgrains and spices, annotations and stories, recipes from festive celebrations, traditional preparations from grandmother’s diary and adaptive recipes from food-scarce and conflict-ridden zones. Also, memory drawings, diaries, napkins along with hand-drawn cartographies of urban villages Khirki and Hauz Rani from where ingredients were sourced for various Pop-up Kitchens.

Artists Sreejata Roy and Mrityunjay Chatterjee says, “Our method at the lab was to rotate the tasks of food preparation, i.e., to have one dish from each cuisine tradition cooked daily, often focusing on a common ingredient or a theme, and then to present these dishes collectively at a monthly Pop-up Kitchen at different sites, where local people are invited to share the meal and encouraged to interact with the project members. Within the lab, pragmatic discussions about particular traditional foods seamlessly expand into wider narratives about displacement, migration and memory, and how these variables compel resettled families to willingly/unwillingly adopt new food habits, occasionally give up old ones, and adapt embedded, hereditary culinary customs to new realities.”

Not all members of the Kitchen Living Lab speak each other’s language, yet are able to actively communicate vis-à-vis essential cooking information and emotional experiences associated with their traditional foods. As speakers of Arabic, Dari, French and various native dialects from their places of origin, they rely on an intuitive, flexible, amalgamated vocabulary of words, gestures, facial expressions, similar regional socio-linguistic codes, digital media and idiomatic translations by those among them who do have some broader knowledge of the various languages in use within the group. They also frequently draw from a lexical cache common to the different languages, and this enables fragmentary utterances to be layered and honed into comprehensible meaning.

According to curator Akansha Rastogi, “The circuitry, negotiations, sharing and the models of living proposed by migration suggest a non-rigid or fluid sense of the word ‘community’, attentive to its temporariness, elasticity and the contradictions of forging one. This group of transient residents, passing through and living in Delhi, come from Somalia, Congo, Ethiopia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Nepal and Bihar, and through a creative invitation of cooking generate an affirmation that didn’t exist before.”

She further notes, “Over and over again I leap into this place, seemingly empty yet woven, the space in-between as the group sits around, which can usually be measured with threads of a daree or is at times clad in anonymity. As the interactions from the kitchens of Khirki migrate into artistic thinking and a contemporary art space, these daily mundane actions perhaps lose some of their transformative potential. Yet also become a means for recalibrating micro-collectivities which are formed out of displacement, where food could be is a tool to blend different worlds, cultures, tongues and geographies.”

The project ‘Museum of Food, A Living Heritage’ by Revue is supported by Prince Claus Fund and British Council, and organised in collaboration with BOSCO Delhi Initiatives UNHCR and Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. The exhibition opens with live music performances by Rous Band, Aya Nazari and Noella, followed by delicious home-cooked snacks from Afghan, Iraqi, Congolese and Somali cuisines.

_0.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)